There are certain generally-accepted views about the Chinese economy that are not entirely correct which can lead to misunderstandings about the market potential for European companies operating in China. Incorrect interpretations of the economic and social landscape may lead to poor investment decisions or ill-thought-out marketing plans.

There are certain generally-accepted views about the Chinese economy that are not entirely correct which can lead to misunderstandings about the market potential for European companies operating in China. Incorrect interpretations of the economic and social landscape may lead to poor investment decisions or ill-thought-out marketing plans.

In this article, Michele Geraci, Head of China Programme at the Global Policy Institute (GPI) and professor of finance at Zhejiang Univeristy and Nottingham University, China, examines two topics which he says are prone to such misconceptions: Chinese saving rates and GDP growth. The scenario he presents is far from the commonly-held belief that China is a market with 1.3 billion potential consumers waiting to be tapped. He also says that the anticipated slowdown in China’s GDP growth could actually be a positive development, provided the ‘quality’ of GDP improves.

One of the greatest myths that I often hear is that Chinese people have a high level of savings and, therefore, it should be relatively easy for European exporters to tap into this potential market. Unfortunately Chinese individuals are not big savers and, in any case, the little that they save is not likely to be spent.

One of the greatest myths that I often hear is that Chinese people have a high level of savings and, therefore, it should be relatively easy for European exporters to tap into this potential market. Unfortunately Chinese individuals are not big savers and, in any case, the little that they save is not likely to be spent.

This misunderstanding arises from an incorrect reading of how national accounts work: in general, we look at GDP broken down according to the expenditure approach (i.e. GDP is equivalent to the sum of investments, consumption and net export). We know that the consumption component in the Chinese economy is low — about 49 per cent of GDP at the end of 2011. Using the familiar concept that what is not consumed is saved, savings then represents 51 per cent of GDP. The problem is that the saving rate thus calculated is the aggregate saving rate for the whole economy and not the personal saving rate, because that figure also includes government savings and other items.

Hence, the general conclusion that the average Chinese person saves 51 per cent of their income is incorrect. In order to obtain the actual amount of personal savings we must turn our attention to the household survey that provides the relevant figures. (It should be noted that the GPI takes no responsibility for the accuracy of these figures but they do represent the best information that we have access to).

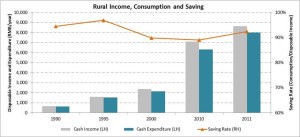

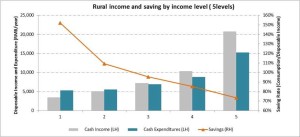

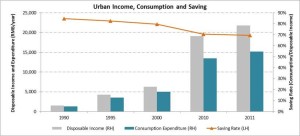

The four charts provided show the historical data series of personal income and expenditure for both rural and urban citizens over two decades and the current breakdown according to income level. They provide some interesting facts, and paint a different picture than that of the national accounts.

Figure one tells us that half of the population — those in rural areas — spend almost all the money that they earn and their saving rate is very low (eight per cent). Therefore, they have limited potential for additional expenditure. As a result, a foreign company that wishes to tap into this market should offer substitute products and encourage those consumers to shift their expenditure from current products to, say, European ones. Unfortunately, these rural residents spend most of their income on food and clothing and price is their main decision factor: therefore it is going to be quite difficult for a European product to have a price point that is more attractive than the locally produced ones; even offering a product of a better quality may do little to swing consumer preferences.

Figure two displays rural saving rates broken down by income levels and we see that only the top two income quintile have some spending power. We can discount the idea of selling them credit cards, therefore the rural market really leaves little potential.

The situation looks a little better for the urban citizens who, on average, save about 30 per cent of their income (see figure three). However, we must not over estimate the value of this figure: figure four — urban saving rates divided by eight income levels — tells us that the bottom two earners (15 per cent of total urban population) spend almost everything they earn.

As income level grows, saving rates increase, as expected—if one earns a million dollar a day he cannot spend a lot and, even in China, there is a limited number of luxury handbags that a lady can purchase. Furthermore, the recent anti-extravagance policy introduced by President Xi Jinping may dampen demand for luxury products.

Therefore, stripping out top earners and bottom earners, we are left with the so-called middle class, representing about 60-70 per cent of the urban population, or 30-35 per cent of the total population. Those people spend 75 per cent of what they earn, thus leaving 25 per cent of their income as a potential market to tap in to. In addition, because of the lack of social security net and, increasingly, uncertainty about future economic growth, there is a large component of precautionary savings that is not going to be easy to tap into, although the health or life insurance markets may be exceptions, if/when they become accessible en-masse to European companies.

In summary, the potential target market could be as little as one third of the population, and their potential additional expenditure is about 25 per cent of their income. Just to be clear, this is still a large number and China remains an attractive market, but this potential is very different from the initial assumption that there are 1.3 billion people who save half of their income and are lining up to purchase European products.

One way to increase consumer spending to is to increase wages, a view shared by our friend Michael Pettis of Peking University, one of the most vocal economists in this area. And this brings me to the second point of this article: GDP growth.

GDP growth in China is mainly driven by government investment and the faster the GDP growth, the more imbalanced the economy becomes. This is because the contribution to GDP from consumption tends to decrease, even if, in recent months, this trend seems to have improved. Using corporations’ annual results as a metaphor, and imagining that a country’s GDP corresponds to a company’s revenues, Chinese ‘revenues’ are of a low quality. It is as if, say, a retail company grew its sales volume by increasing the number of shops: total revenues naturally grow, but same-store revenues may not and, even more worryingly, return on investment (ROI) may be negative (and I suspect this is the case for most Chinese investment projects).

This GDP growth model, that favours large infrastructure projects, works well for resources and raw materials-rich exporters; unfortunately, countries like Australia, Chile and Russia, do not belong to the European Union. But the current model has benefited countries like Germany that — thanks to the artificial system called the eurozone — has successfully exported its technology products to China.

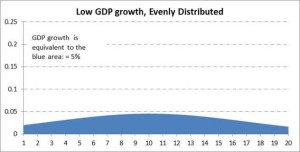

The challenge for China is to improve the quality of its GDP and make it more dependent on internal demand. This is process that will take several years, but it must be done, and the sooner the better. There are many ways that such rebalancing can be achieved. The one I favour is to, a) lower the GDP growth while, b) simultaneously spreading the economic growth more evenly across the population. The following charts below are a conceptual illustration of this idea.

Figure five depicts the current situation in China: a high level of GDP growth (for example eight per cent) accompanied by a high degree of concentration of such growth in the hands of a few ‘groups’, represented by the x-axis (e.g. coastal or inner provinces, city or urban residents, construction or retail sector etc); it shows that, even if growth is high (represented by the total blue area under the curve), it is concentrated only in the hands of a few (groups 10 to 20, along the x-axis).

An alternative, possible future scenario is shown in figure six whereby GDP growth rate slows down to perhaps five per cent (the total blue area is now smaller), but this growth is better distributed across all sectors, across all provinces, across all income groups and so on. Such a new and more harmonious growth model can be achieved in several ways. Fundamentally, the aim is to let as many groups as possible benefit from economic growth.

Bearing in mind the previous point I illustrated regarding the lack of spending potential of Chinese consumers, let’s ask ourselves this question: if you operate a business that needs to target Chinese consumers, would you prefer a scenario with a high GDP growth but with benefits limited to only a few groups, or sacrifice overall growth in exchange for being able to reach a wider market? Depending on the nature of the goods being sold the second scenario may well be more attractive.

In conclusion, we tend to overestimate the spending potential of the average Chinese consumer which is, instead, limited by the low level of income and concentrated only within a few groups. For consumption power to increase, personal income must be more evenly distributed and this can be achieved, even — and perhaps more easily — if GDP growth slows down and the ‘quality’ of GDP improves.

The Global Policy Institute is a Research Institute that was founded in August 2006 to analyse the issues of globalisation and to formulate innovative policy solutions. Based in Jewry Street in the City of London, it draws on both a rich pool of local academic and business professionals and its extensive international connections. The Institute gives non-partisan guidance to policymakers and decision takers in business, government, and NGOs.

Michele Geraci is also Senior Research Fellow and Adjunct Professor of Finance at Zhejiang University, and Visiting Assistant Professor of Finance at Nottingham University Business School, China. Prior to coming to China, Michele worked in the investment banking industry for more than a decade.

Michele,

What mechanisms would you propose for flattening out China’s income distribution? And how will this increase consumption, since you say that low income people do not consume. Any marginal increase in their income will lead to greater savings than s[ending; as a corollary decrease in urban middle class consumption?

Consumption growth in China (now at roughly a 13% annual increase) is a middleclass urban phenomenon. Cities, not rural areas, consume. Increasing consumption depends upon continued urbanization and middle class growth through the market dynamics of city economies.

Your proposal may have the social merit of equality, but it will decrease economic activity and consumption.

Milton Kotler . .

; .