More action needed, not more action plans

While doing business in China has always required a high degree of flexibility in order to adapt to the rapidly changing environment, companies previously viewed the complex challenges they encountered as the ‘growing pains’ of an emerging market. There was a common perception that the difficulties faced were worth bearing in exchange for access to a large and dynamic market, world-leading manufacturing clusters and comparatively cheap labour. With the risks of doing business mounting and the rewards seemingly decreasing, many investors are now confronted with the reality that their approach may require a substantial strategic rethink.

The central concern for European Chamber members is China’s economic slowdown. However, several other factors are dragging on business confidence, including perennial market access and regulatory barriers; a highly politicised business environment; lacklustre domestic consumption; overcapacity; the persistence of ambiguous rules and regulations; and the government’s continued focus on national security and developing a high degree of self-reliance.

A sentiment is emerging at company headquarters (HQs) and among shareholders that the returns on China investments are no longer commensurate with the risks faced. Profit margins in the country are equal to or below the global average for approximately two thirds of European Chamber members, and pessimism about future profitability is at an all-time high. With many other markets now offering greater predictability and legal certainty along with at least the same returns on investment, continuing to invest at previous levels in China is simply becoming harder to justify.

There are indications that foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) have already begun adjusting their investment strategies. Foreign direct investment (FDI) into China decreased by 29.1 per cent year-on-year during the first half of 2024. Furthermore, the volume of investments made by European Union (EU) and American firms is now roughly half that of a decade ago, with smaller multinational companies and small and medium-sized enterprises in particular opting to invest elsewhere.

In past years, this shortfall would have at least been partly offset by reinvestments – businesses using profits earned in China as opposed to capital injections from their HQs to fund projects. However, this metric is also trending downwards, as is the number of businesses that plan to expand their China operations.

In tandem, the nature of the FDI that the country is still able to attract is changing, as focus shifts from cost and efficiency considerations, to building resilience and ensuring the continuity of company operations. New investments are increasingly defensive, geared towards creating China-specific value chains, separate IT and data storage systems, localising business functions, and enhancing compliance capacity, rather than beefing up China research and development or capturing market share. These kinds of investments will neither create new jobs nor drive innovation.

Similar defensive trends can be seen when it comes to diversification of supply chains. European Chamber members have begun both offshoring and onshoring, often at additional cost and loss of efficiency, as they seek to mitigate risks.

These changes are by no means a sign that European companies are running for the exit, but they do represent a strategic shift towards siloing China operations from the rest of the world. While this creation of autonomous, and sometimes divergent, systems may provide greater operational resilience, it will likely set the EU and China on course for a future of reduced engagement resulting in missed opportunities.

Reform plans need to be backed by meaningful implementation

At the start of the new millennium, reform plans announced by the Chinese Government were seen by foreign companies as credible, following years of concrete improvements to the business environment in the periods immediately preceding and following the country’s World Trade Organization accession. Now, after more than a decade of largely unfulfilled pledges, doubts over China’s commitment to reform are increasing.

It is against this backdrop that the State Council’s 13th August 2023 Opinions on Further Optimising the Foreign Investment Environment and Increasing the Attraction of Foreign Investment (Opinions)[1] was initially hailed as a potential turning point. While not a silver bullet for the headwinds China’s economy is facing, the European Chamber believed that full implementation of the Opinions would help prevent a further deterioration in business confidence and provide a solid foundation to build on.

One year on from the document’s publication, momentum has been lost.

To quantify this, the European Chamber asked the members of its 50 working groups, sub-working groups and fora, as well as its seven local chapters, to provide feedback on the progress they have seen on the measures so far.

This ‘reality check’ makes for sober reading. While the Opinions contain several big-ticket items that could really move the needle, limited implementation has taken place. With a few exceptions, the areas in which progress has been made have been those that will have little material impact on business, or which are too narrow in scope to meaningfully address the challenges faced by foreign companies.

The key takeaways of the Position Paper’s analysis are summarised below, organised across six thematic areas:

- Market access and procurement: Actual progress made has so far largely been incremental and restricted to initiatives of limited sectoral and geographical scope, while foreign companies continue to face discrimination in China’s procurement market.

- Human resources (HR) and business travel: Early breakthroughs were seen through the extension of China’s preferential individual income tax policy for foreign nationals and via the waiving of visa requirements for citizens from several EU Member States. However, such developments represent low-hanging fruit and have yet to be followed by additional action that addresses the main HR-related concerns of European companies.

- Digital and cyber: Some initial momentum has been built in this area following the revision of China’s regulations for cross-border data transfer. At the same time, there remains the need for upcoming rules to not be defined in an expansive manner,[2] as well as for industry-specific regulations to be better aligned with China’s revised Provisions on Promoting and Regulating Cross-border Data Flows.[3]

- Access to green energy: Incremental progress has been made, but more needs to be done if FIEs are to meet their global corporate decarbonisation goals, which for many is needed to legitimise their continued presence in the China market.

- Intellectual property rights (IPR): Practical challenges continue to undermine the enforcement of IPR in China, while little progress has been made on sectoral-level challenges.

- Investment promotion and facilitation: Concerted efforts have been made to increase government-industry dialogues. However, in many instances, such dialogues have not produced results. There are several points in the Opinions related to the provision of support and incentives for investment in China, but their impact has been largely underwhelming, in part due to the related text lacking ambition and specificity.

The 2024 Third Plenum: Little to suggest a course correction is imminent

With limited progress made on the Opinions, the foreign business community had been looking to the Third Plenum of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party for signals that their concerns would be addressed, in particular policies aimed at boosting domestic demand, a renewed focus on reform and opening up, and greater weight being given to market forces.

However, there was little indication provided at the session that a course correction will be forthcoming.

The Third Plenum Decision continues to promote investment in manufacturing as a key driver of China’s economic development, albeit under the moniker ‘new quality productive forces,’ all while providing little concrete detail on how domestic consumption will be stimulated .

Second, while the document states that that the market should play “the decisive role in resource allocation”, it also calls for state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and state capital to “get stronger, do better and grow bigger.” At the time of writing little indication has been provided on how the authorities will square this circle.

Third, the Decision places an increased emphasis on national security, with a whole chapter dedicated to the subject. While all state actors must do what is necessary to ensure economic security, the concern among FIEs is that China’s prioritisation of security could lead to policies that go beyond legitimate concerns and create insurmountable business risks. European companies are already struggling to understand their compliance obligations under a slew of recent security-related legislation.

The costs of failing to act

The main cost of failing to take further action to address business concerns more comprehensively, is that the negative trends witnessed over the past few years can be expected to continue.

At the business level, this would equate to a further loss of investment for China, the continued siloing of supply chains and company operations, and the current fissure between HQs and their China operations expanding to become a chasm.

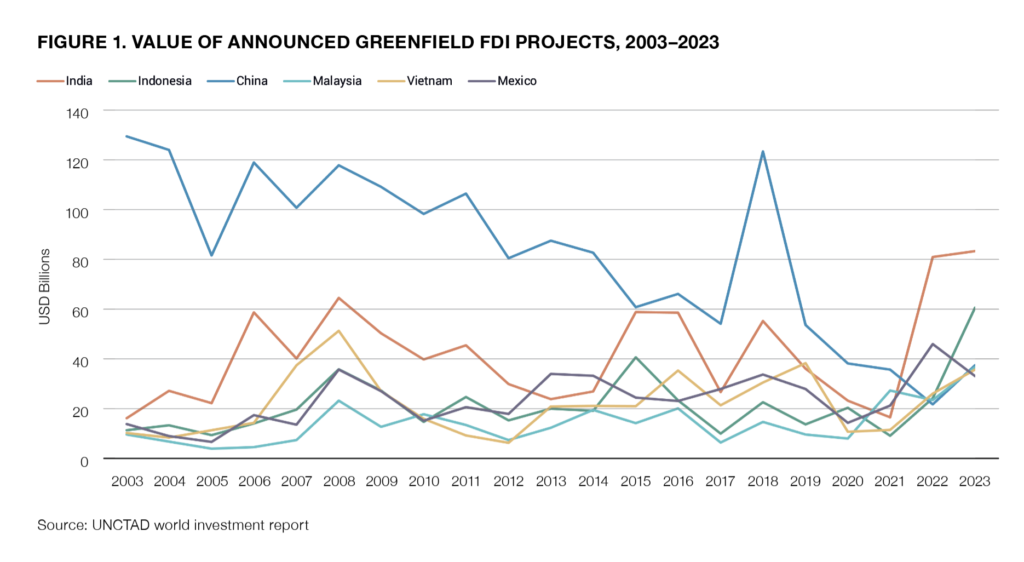

Beijing would also be opening the door wider for other regions to court investment at its expense. The graph below—which shows annual greenfield FDI flows into China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, India and Mexico between 2003 and 2023—illustrates that this dynamic is already in play, and that it intensified from 2018 onwards.

At the intergovernmental level, failure to implement meaningful economic reforms will likely result in an increase in EU-China tensions. The EU has already begun taking a more assertive stance towards China on key areas of concern to European business in China. Moreover, it now has the legal muscle to exert real pressure, having introduced in recent years a set of tools aimed at protecting the integrity of its Single Market, and ensuring reciprocal market access and a level playing field for European companies operating in third markets.

Tensions could be dialled down if the Chinese authorities were to fully implement the measures detailed in the Opinions. While this would not be a panacea, it could turn the tide and begin the process of rebuilding investor confidence in the China market.

If China is to re-establish itself as the preferred destination for foreign investment, then significant additional steps will also be needed to improve the business environment. To this end, the Chamber’s latest Position Paper puts forward 1,024 detailed and constructive recommendations to the Chinese authorities on how this can be achieved.

Robbie Jarvis is a Policy and Communications Manager at the European Chamber and lead pen of this year’s Position Paper.

The European Chamber’s Position Paper 2024/2025 is available to download free from the Chamber’s website. Please visit: <https://www.europeanchamber.com.cn/en/publications-archive/1269/European_Business_in_China_Position_Paper_2024_2025>

[1] Opinions on Further Optimising the Foreign Investment Environment and Increasing the Attraction of Foreign Investment, State Council, 13th August 2023, viewed 13th September 2024, <https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/202308/content_6898048.htm>

[2] Examples include upcoming rules for what constitutes ‘important data’ and ‘sensitive personal information’.

[3] Provisions on Promoting and Regulating Cross-border Data Flows, Cyberspace Administration of China, 22nd March 2024, viewed 14th October 2024, <https://www.cac.gov.cn/2024-03/22/c_1712776611775634.htm>

Recent Comments