As Europe enters a summer of political transition, one of its latest efforts to advance sustainability and human rights has not gone unnoticed. Jeremy Azzopardi, a student at the Western Academy of Beijing, investigates the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD).

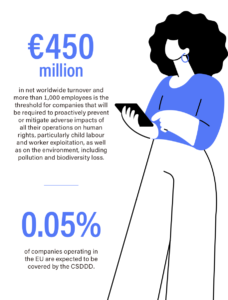

On 23rd February 2022, the European Commission proposed its Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) seeking to advance the EU’s sustainability and social goals worldwide. Companies with at least euro (EUR) 450 million in net worldwide turnover and more than 1,000 employees will be required to proactively prevent or mitigate adverse impacts of all their operations on human rights, particularly child labour and worker exploitation, and on the environment, including pollution and biodiversity loss.[1] Some companies will also need to craft business strategies in line with the 1.5 °C global warming temperature limit rise of the Paris Agreement. Penalties for violating the directive could exceed five per cent of net worldwide turnover.[2]

The directive is expected to have far-reaching impacts on both European and foreign businesses operating in Europe, with the rules obliging a significant corporate duty to prevent damage from a company’s own operations subsidiaries, as well as along its entire value chain. Commenting on the directive’s potential to promote European ideals globally, Věra Jourová, president of the European Commission for values and transparency, said: “This law will project European values on the value chains, and will do so in a fair and proportionate way.”[3] However, the CSDDD’s all-encompassing scope has been drastically revised following concessions and political wrangling.

Backdoor dealings at the Council

Several countries reportedly expressed concern at the European Commission’s original proposal. France lobbied for extensive changes to the text, beginning with a successful effort in December 2023 to exclude financial institutions.[4] Italy and Germany voted against numerous versions of the text fearing an excessive impact on smaller businesses, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SME), while holding concerns about its broader bureaucratic burden. Following compromises and sweeping changes, Italy cast the decisive vote in favour at the European Council in March 2024, while squabbling among members of Germany’s coalition government led to its continued abstention.[5]

Finland had reservations regarding the directive’s civil liability provisions, which would have allowed victims to file class action lawsuits to recover damages.[6] The Finnish Government noted that such a legal framework would be incompatible with existing domestic law. Together with later-removed clauses holding company directors directly accountable for damages, the civil liability provisions were clarified and watered-down.

A lose-lose for businesses and NGOs?

Industry organisations and business groups including Business Europe, Eurochambres and the German Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DIHK), have denounced the directive for fragmenting the internal market, burdening companies with impractical obligations, disrupting supply chains and increasing costs.[7]&[8] Foreign business organisations, including AmCham and the China Chamber of Commerce to the EU, have joined calls to reduce the directive’s sweeping compliance and administrative costs, complexity and legal risks, cobbling together an unlikely opposition coalition.[9]

Businesses have repeatedly highlighted the directive’s scope, legal risks and the lack of consideration for potentially conflicting third-country legislation as chief concerns. They warn that the obligations will damage business competitiveness, both inside and outside of Europe. The directive may disrupt the level playing field and could place European companies operating abroad at a competitive disadvantage, with a new need to fulfil lengthy due diligence obligations. With increasing barriers to entry for European businesses, the burden of due diligence may dissuade third-country local firms from working with European companies as partners. Europe is also likely to suffer from reduced foreign direct investment, with the CSDDD imposing sweeping rules that could be avoided by entering other markets.

Environmental and labour groups have rallied behind the CSDDD but criticised the European Council for watering-down the directive, with the CSDDD only expected to cover 0.05 per cent of companies operating in the EU.[10] More than 100 NGOs issued a joint statement in February 2024 pointing the finger at member states, naming and shaming France and Germany for derailing negotiations and for failing to consider companies’ impacts on human rights, workers, ecosystems and indigenous peoples.[11] Friends of the Earth Europe similarly criticised the directive for not including obligations related to emission reductions.[12]

What’s next?

With the CSDDD passing the European Parliament on 24th April 2024, the directive is now all but law, requiring only the rubber-stamping of the EU Council of Ministers in May. But Europe is likely nowhere near ready for the law’s wide-ranging impact, which due to the large footprint of European business is likely to affect every corner of the globe. It remains to be seen whether the EU will succeed in advancing European values or whether the directive will simply drive companies out of emerging markets, reducing Europe’s global influence.

Such extensive due diligence throughout entire value chains could pose a particular challenge for European companies operating in China. Expansive domestic legislation, such as the recently broadened state secrets and anti-espionage laws, puts companies working in strategically critical fields at acute risk, with the possibility of criminal liability in China as they seek to fulfil the EU directive. The rules will also force European companies to undertake comprehensive investigations in politically sensitive regions, such as Xinjiang. Companies could view such obligations as an excessive risk, forcing them to leave certain areas, relocate production, reduce market share or even exit enormous markets like China altogether.

Europe has been increasingly criticised for exploiting its regulatory influence, often called the ‘Brussels effect’, with some claiming that the EU’s recent climate measures are a form of neo-imperialism on the Global South. The EU should exercise caution in its regulatory and climate agendas, ensuring an inclusive and consultative approach with all stakeholders, including international partners and European businesses. Only time will tell whether the CSDDD will serve its intended purpose.

Jeremy Azzopardi is a high school student from

Malta currently pursuing the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme at

the Western Academy of Beijing. Born and raised in Beijing, he serves as

Student Council President and is passionate about politics and the environment.

He is interested in China’s foreign relations, the European Union and climate

politics.

[1] Blenkinsop, P, EU backs supply chain audit law after Italy switches sides, Reuters, 15th March 2024, viewed 16th May 2024, <https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/eu-envoys-clear-proposed-supply-chain-audit-law-belgian-presidency-says-2024-03-15/>

[2] Just and sustainable economy: Commission lays down rules for companies to respect human rights and environment in global value chains, European Commission, 23rd February 2022, viewed 16th May 2024, <https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_1145>

[3] Ibid.

[4] White, S, and Hancock, A, France Seeks Weaker EU Due Diligence Rules for Banks, Financial Times, 13th December 2023, viewed 16th May 2024, <https://www.ft.com/content/18d52021-c551-4a19-95ff-6b5c864c83bf>

[5] Blenkinsop, P, EU backs supply chain audit law after Italy switches sides, Reuters, 15th March 2024, viewed 16th May 2024, <https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/eu-envoys-clear-proposed-supply-chain-audit-law-belgian-presidency-says-2024-03-15/>

[6] McGowan, J, Fate Of EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Law Worsens As Finland Pulls Support, Forbes, 7th February 2024, viewed 16th May 2024, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/jonmcgowan/2024/02/07/fate-of-eu-corporate-sustainability-due-diligence-law-worsens-as-finland-pulls-support/?sh=7c7eadc5431d>

[7] EU due diligence could leave companies between a rock and a hard place,BusinessEurope, 12th December 2023, viewed 16th May 2024, <https://www.businesseurope.eu/publications/eu-due-diligence-could-leave-companies-between-rock-and-hard-place>

[8] Blenkinsop, P, EU backs supply chain audit law after Italy switches sides, Reuters, 15th March 2024, viewed 16th May 2024, <https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/eu-envoys-clear-proposed-supply-chain-audit-law-belgian-presidency-says-2024-03-15/>

[9] EU failing to endorse CSDDD a response to apprehensions widely shared the business communities: Chinese commerce chamber, Global Times, 1st March 2024, viewed 16th May 2024, <https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202403/1307986.shtml>

[10] Corporate sustainability and Due Diligence Directive: the good, the bad, and the ugly, European Economic and Social Committee, 15th March 2024, viewed 16th May 2024, <https://www.eesc.europa.eu/en/news-media/press-releases/corporate-sustainability-and-due-diligence-directive-good-bad-and-ugly>

[11] European Union: Joint Civil Society Statement Reacting to Lack of Majority in COREPER on CSDDD, Amnesty International, 28th February 2024, viewed 16th May 2024, <https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/ior60/7760/2024/en/>

[12] EU Council endorses corporate accountability law after years of negotiations and delays, Friends of the Earth Europe, 15th March 2024, viewed 16th May 2024, <https://friendsoftheearth.eu/press-release/eu-council-endorses-corporate-accountability-law-after-years-of-negotiations-and-delays/>

Recent Comments