Why ‘coopetition’ will be the new norms for MNCs operating in China

Why ‘coopetition’ will be the new norms for MNCs operating in China

As China adapts to slowing economic growth, foreign investors are focusing on ‘quality growth’ over mass expansion. Though many industries have seen foreign equity caps lifted, Keat Lee of Deloitte Consulting explains how overseas firms continue to put more emphasis on merging strengths with local partners rather than merely acquiring market access.

Views on inbound investment

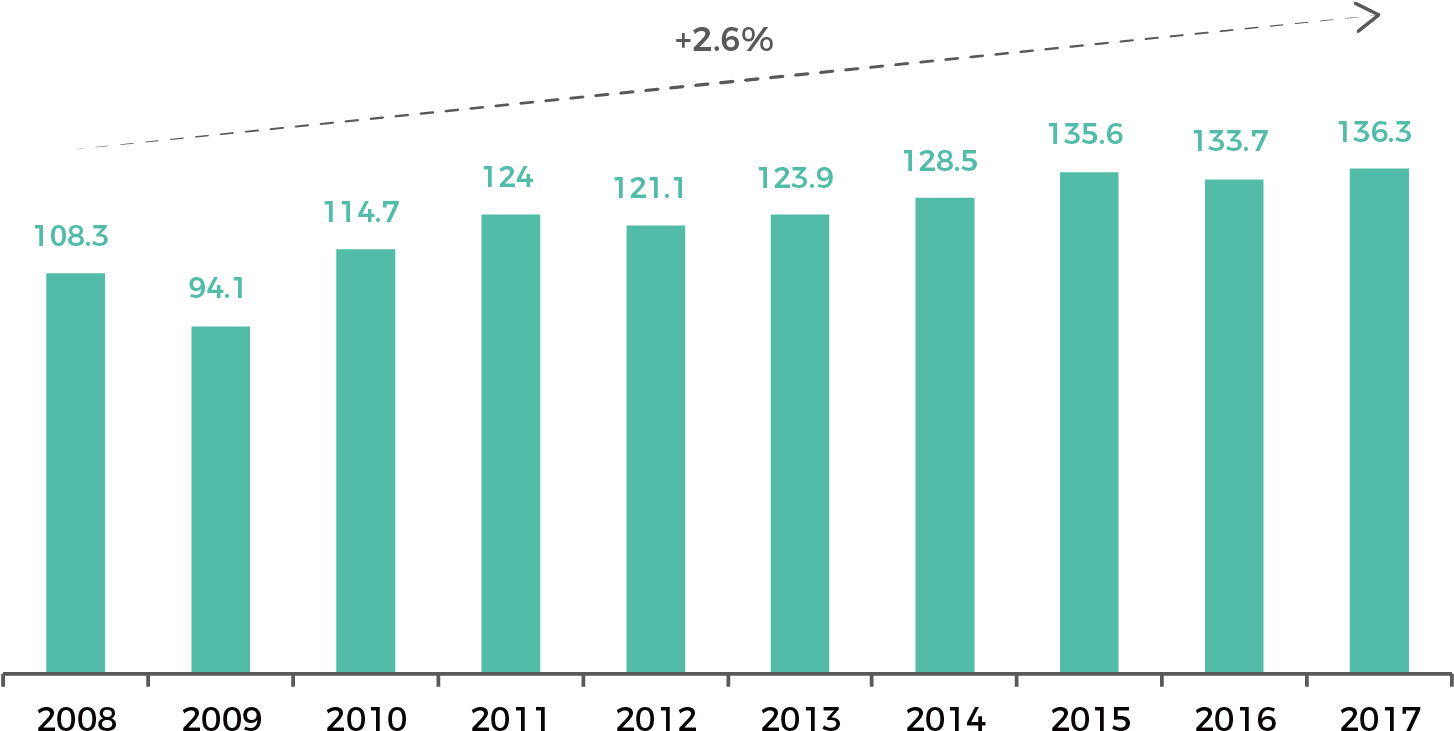

Foreign direct investment (FDI) in China has grown steadily over the past decade, reaching United States dollars (USD) 136 billion in 2017 (see Chart 1). This has been attributed to the country’s increasingly favourable regulation and policy environment and stable economic growth. That same period also saw investment gradually shift from labour intensive/resource-orientated industries to high-tech/artificial intelligence-related sectors.

FDI in high-tech manufacturing has increased, with compound growth rates averaging at 12.4 per cent over the past ten years.[1] That comes as leading players in innovative technology—such as telecoms (5G), semiconductors, smart manufacturing, smart health care and future mobility—build up their presence in the Chinese market. Meanwhile, the increasing FDI in tertiary industries, especially high-tech services such as information and intellectual property (IP)-related services, indicates a more tech-orientated Chinese investment environment.

Chart 1 Inbound Investment in China[2] Unit: billion USD

One key driver of the upward trend is the Chinese Government’s policy of opening up the market more, enabling overseas firms to participate in industries once reserved for domestic players. One typical example of this is the Special Administrative Measures for Admittance of Foreign Investments, revised in 2018 to confirm that foreign equity limits in automotive joint ventures (JVs) will be gradually removed. The easing of restrictions will apply first to electric and commercial vehicles, and expand to passenger vehicles by 2021.

Trends in FDI into China from the European Union have also had an upwards slant. 2017 saw investments worth USD 8.3 billion, up from USD 5.1 billion in 2008—that’s an increase of more than 50 per cent over the decade. In contrast, US investment rates remain relatively stable, which is partially due to the negative impact of the trade war. The tension between the two giant economies has also led some US companies to minimise risks by selling part of their China operations. For example, Eli Lilly sold the rights to two types of antibiotic medicines, along with a manufacturing facility in China, to avoid any negative impact from new policies that are more favourable to generic drugs.

Meanwhile, as trade tensions still persist, it is worth noting two trends in particular currently emerging in the business market: joint ventures and ‘coopetition’.

Joint ventures

Although foreign equity limits joint venture model will persist. This system can help firms adapt to and navigate the complex China regulatory landscape by cooperating with long-term domestic partners. For instance, have been lifted in certain industries, for multinational corporations (MNCs), the observers may have noticed waves of semiconductor companies setting up JVs with local partners in order to seize expansion opportunities in China.

‘Coopetition’

’Coopetition’ is going to be the new norm in the Chinese business environment. Up until now, the JV model was one of ‘loose cooperation’ with the theme of ‘offering market access in exchange for management superiority and technological know-how’. Previously, it was common for foreign companies to deem local partners simply as a sales channel, which resulted in low levels of integration between the entities. As local companies develop their own R&D capabilities, the investment environment in China is becoming more competitive for MNCs. Therefore, a once competitive relationship may turn collaborative through deeper cooperation in R&D areas. Specifically, it means:

- From a product development perspective, ‘co-development and co-owned IP’ orientated to the China market will become the new norm; and,

- The ability to cultivate local teams with local market know-how, compliance and technology requirements will be vital.

Proper execution of the ‘coopetition’ model could help MNCs avoid cannibalisation of their existing global products.

For many MNC executives, the top concern over the co-development R&D model is IP infringement. Many fear that this, coupled with China’s data privacy and security requirements, would erode their global competitiveness. While the Chinese Government has stepped up its efforts to protect IP, there is still a strong belief among MNC executives that data security would offer insufficient protection. This leads to hesitation in investing or bringing the latest technology or IP into the Chinese market.

Views on outbound investment

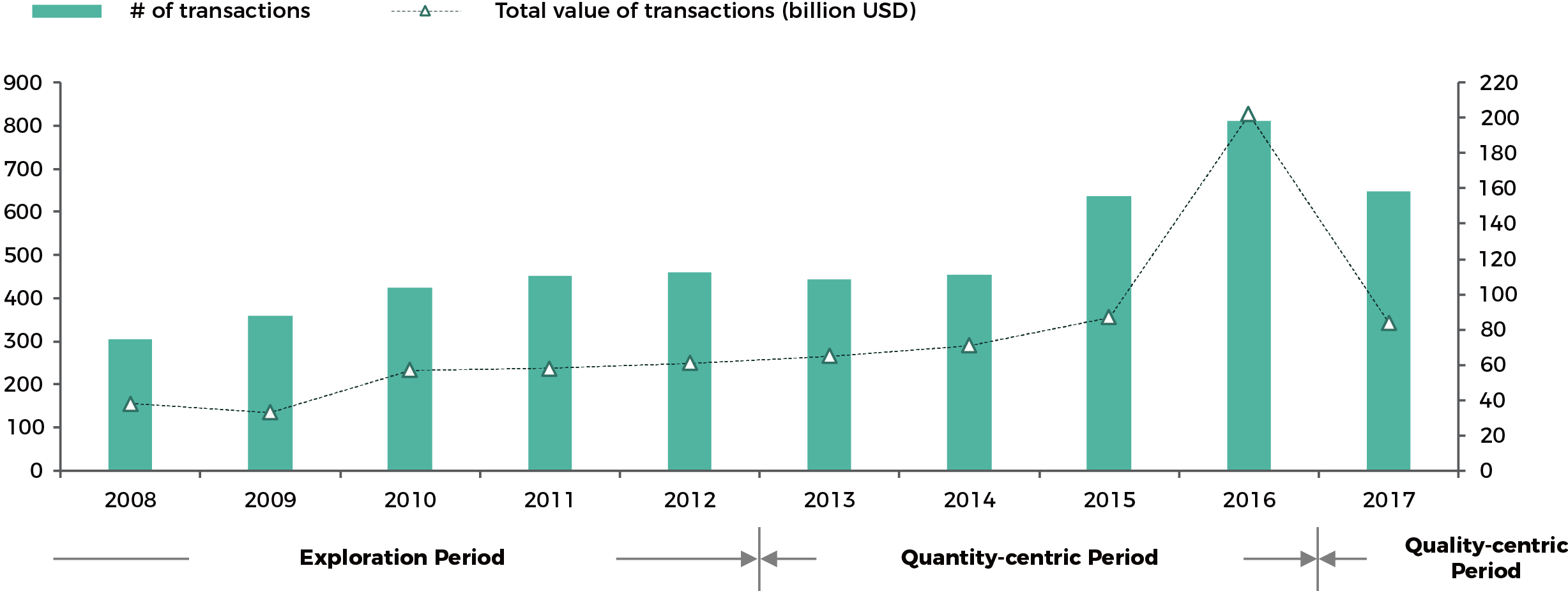

China’s cross-border investment can be broken down into three main periods. The initial phase began in 2008 and can be defined as the ‘exploration period’. At that time, large state-owned enterprises focused on accumulation and expansion in pillar industries such as oil and gas or mining and steel, with the aim of securing global commodity resources.

Since 2013, as the economy remained strong and with the introduction of the Belt and Road Initiative, mass numbers of Chinese companies have participated in cross-border investment to gain brand and technology competitiveness. This era could be regarded as the ‘quantity-centric’ period, with investors prepared for potentially low returns. This trend reached its peak in 2016 as diversified investors (stated-owned/private companies and local funds) penetrated a variety of industries.

Chart 2 China Cross-border M&A Transactions[3]

# of transactions refers to all transactions made in the year and the total value excludes undisclosed deals.

More recently, the ‘quality-centric’ period has seen more rational investors take the stage. With more experience in overseas deals and risk control, this group focuses on assets with synergy value. A growing number of Chinese companies realise the importance of post-deal integration, risk control, culture alignment and talent cultivation.

Meanwhile, government policies and regulations are also playing a part in cooling down the global market. Protectionism has led the US and certain European countries to restrict foreign investment in high tech and state security-related areas.

In this new ‘quality-centric’ period, China’s cross-border M&A investments have evolved to be more market-orientated, diversified and with more emphasis on strategic planning and achieving synergy. Compared to SOEs, private enterprises—or ‘people enterprises’ as they’re called locally— have become more involved in consumer products, industrial goods, travel and entertainment industries in recent years. Many Chinese companies are now seeking minority shares in foreign players to improve customer experience and enrich their product portfolio. For example, China Eastern Airlines formed a tripartite alliance with the Air France-KLM group in order to offer an ever-expanding range of services and share non-aviation resources. Another case is that of Tencent obtaining the rights to publish Ubisoft’s PC and mobile games, after purchasing a five per cent stake in the French game company.

In summary, while trade tensions will persist, the fact that the US business community is increasingly putting pressure on their government to reach a deal is building hope that commercial rationale will ultimately prevail. However, this may still not make doing business in China any easier. The data privacy and security rules that require data residence in China may make MNCs hesitant to bring their most valuable or latest IP onto Chinese soil. Having said that, China is putting effort into opening up its market, particularly regarding accelerated easing of restrictions for the financial industry, and reducing JV requirements for the automotive industry. MNCs will still be prepared to plough their tech know-how into the large Chinese market to capture a piece of it. In many Chinese industries, local insight is still essential for success, and therefore JVs as a market-entry approach will persist.

Introduction to the Authors and Deloitte Consulting

Keat Lee is a leading partner of Merger and Acquisition (M&A) Consulting Services with Deloitte Consulting China. He has over 18 years of consulting experience in cross-border mergers and acquisitions, focusing on integration, divestiture planning and post-deal value creation/execution. His experience covers a wide range of industries, including technology, consumer and industrial products, Fintech, petroleum and automotive.

[1] Source: MOFCOM yearly foreign investment reports, MOFCOM, viewed 20th May 2019, http://wzs.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx/; Ministry of Commerce: 60,533 new foreign-invested enterprises set up in China in 2018, Sina Finance, 14th January 2019, viewed 20th May 2019, http://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/2019-01-14/doc-ihqhqcis6126351.shtml

[2] Source: MOFCOM yearly Foreign Investment reports, MOFCOM, viewed 20th May 2019, http://wzs.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztxx/; Ministry of Commerce: 60,533 New Foreign-invested Enterprises set up in China in 2018, Sina Finance, 14th January 2019, viewed 20th May 2019, http://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/2019-01-14/doc-ihqhqcis6126351.shtml

[3] Source: Dealogic, <https://www.dealogic.com/>

Recent Comments