The process of Chinese hospitals adopting a commercial mindset

The process of Chinese hospitals adopting a commercial mindset

Choosing a fair and efficient payment system for hospitals is challenging for health authorities around the word. Calculating healthcare costs is no simple matter and has been complicated even further in China by how fast its medical system has developed. Volker Müller, business manager at the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, looks at reforms in China’s hospital payment systems and outlines the pros and cons of globally adopted payment methods.

The development of China’s healthcare system has reached a turning point. China’s life expectancy and overall healthiness have reached levels similar to middle to high-income countries. In 2016, the ratio of health expenses to the nation’s gross domestic product reached six per cent, higher than Singapore (five per cent) and roughly the same as Poland. Since starting at an extremely low level, China’s healthcare expenses have been growing at an annual double-digit rate. This growth rate is not sustainable, with an increase of expenses preventing further significant improvements to the population’s health. One of the key elements of China’s healthcare reform agenda titled Healthy China 2030 is the reform of hospital financing. This seems to be a rather dull issue, but how hospitals get their money has a direct effect on the quality of health services and the industry’s overall business environment.

Who pays and how?

Calculating the cost of surgery is not an easy thing to do. The main cost factors are: the type of drugs and disposable medical devices; salaries of the medical and administrative staff; the use of medical equipment and facilities; the expected lifetime of the equipment; and costs that occur before and after the operation such as sterilisation of surgical instruments, disinfection of the operation room and disposal of medical waste. From a financial standpoint each surgery is a project not a product. Expenses can only be roughly calculated until after the surgery has been completed and the patient is discharged.

There are basically three different sources to finance hospitals: direct payments by the State (financed by taxes), social or private health insurance and out-of-pocket payments by patients. In most countries, hospital income derives from a mix of these sources. In China, social health insurance pays for approximately 53 per cent of total expenses, while different levels of the government pay about 15 per cent. Unfortunately, patients’ out-of-pocket expenses amount to a fairly high 32 per cent, although these figures vary considerably by province and town/countryside population.

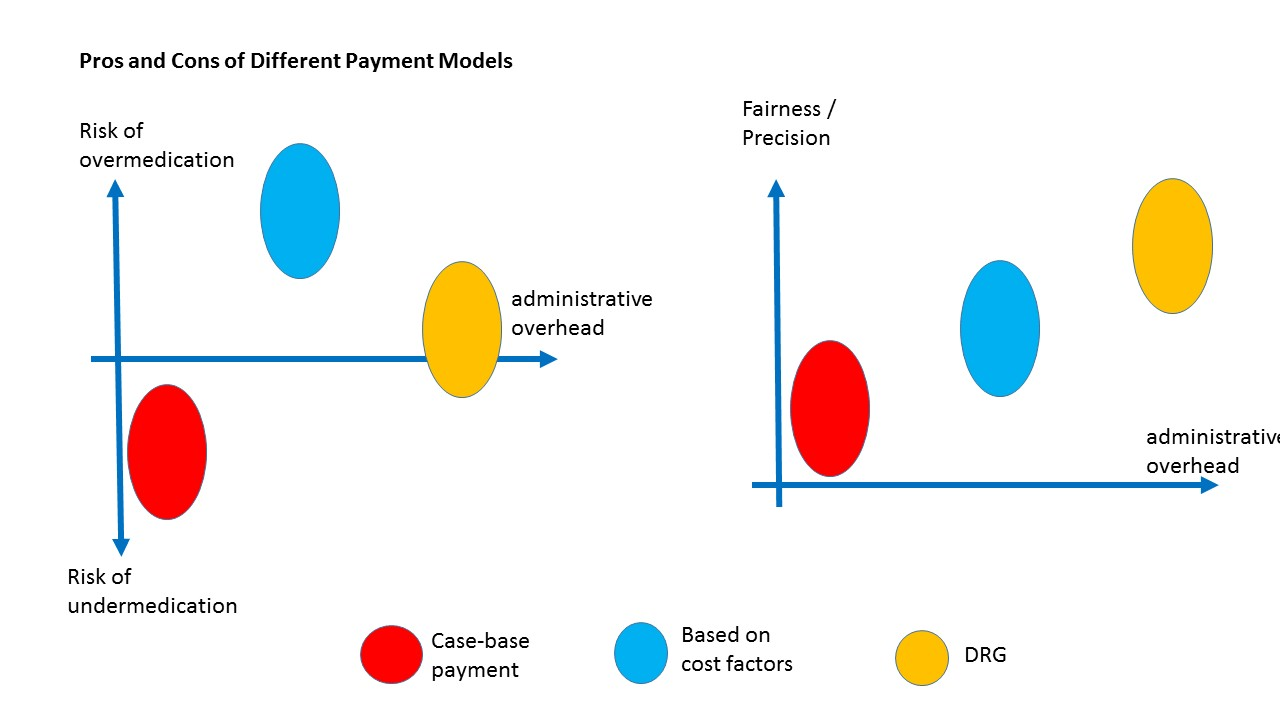

The simplest method for hospitals to gain revenue is through direct financing by the state. A similar type of healthcare financing was used in most Eastern European countries until the late 1980s. An advantage to this type of system is that there is no administrative overhead for calculating the prices for select medical services. The problem with a system like this is the waste and lack of efficiency that comes from an absence of commercial thinking. Other hospital payment systems require a calculation of the estimated cost of treatment. Hospital payment systems need to strike a fair balance between the price of treatment and the amount of time it takes the administration to enforce the policy.

In China, the pricing departments of the provincial Development and Reform Commissions compiled very detailed price lists for different cost factors from a hospital treatment. Some of these cost factors included the cost of the prescribed drugs as well as the use of disposable medical devices and medical equipment.

One major shortcoming of these price lists was the undervaluation of the work done by medical personnel. For each hospital visit the patient had to pay a small registration fee which amounted to only a few yuan. To make ends meet, the hospital was allowed to sell drugs from the hospital pharmacy at a profit with a markup that usually ranged between 20–30 per cent. The consequence from this was the widespread problem of over-medicating – in order to increase the income of the hospital, doctors regularly prescribed medicines that were not needed.

Starting in 2017, almost all provinces in China have banned mark-ups on medicine sold in hospitals. Patients are encouraged to compare prices and may choose to buy medicine in a pharmacy outside the hospital if the prices there are cheaper. As a consequence, drug prices in hospitals have decreased considerably. To compensate hospitals for the lost income, registration fees have increased. Considering that high registration fees may deter low-income patients from seeing a doctor, in some less-developed areas registration fees are kept constant with the government paying the difference. In November 2017, the National Development and Reform Commission published its Opinion on Deepening the Reform of the Pricing System, calling for a ban of mark-ups on disposable medical devices. This new policy was widely welcomed by the public and helped address the problem of overmedication. However, this policy did not remedy the issues that come from taking a non-commercial approach to healthcare. The hospital is still not properly incentivised to choose an economical form of treatment. To control healthcare expenses, in 2017 the National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) introduced a new concept called case-based payment. Treatment of certain common diseases receive a fixed price, which covers all parts of the treatment including drugs, medical devices and labour costs.

This price is independent of the quantity of drugs used and the number of medical devices applied. The NHFPC published a catalogue of 320 common diseases. Each provincial Health and Family Planning Commission (HFPC) selects a minimum of 100 diseases out of the catalogue and sets the price for treatment. In this way, the responsibility for cost control is passed down to the hospitals.

However, case-based payment is also not an ideal solution. Hospitals may be tempted to discharge patients too early and use low-cost medical devices of lower quality. Expenses for different patients may vary considerably. For example, older patients may need to stay hospitalised for a longer period of time which increases the hospital’s expenses without bringing in additional income. It is because of this, that hospitals may try and attract ‘cheap’ patients and reject the ‘expensive’ ones.

However, case-based payment is also not an ideal solution. Hospitals may be tempted to discharge patients too early and use low-cost medical devices of lower quality. Expenses for different patients may vary considerably. For example, older patients may need to stay hospitalised for a longer period of time which increases the hospital’s expenses without bringing in additional income. It is because of this, that hospitals may try and attract ‘cheap’ patients and reject the ‘expensive’ ones.

Two issues, aside from hospital payment, that need to be addressed is the price of treatment being too low and the lack of supervision by health authorities regarding medical services. So far there is only a limited pool of experience to draw upon when it comes to case-based payment in China.

A more elaborate way of utilising case-based payments is by using the so-called diagnostic-related groups (DRG). Originally designed for resource allocation within hospitals, DRGs now are often used to ‘fine-tune’ hospital payments. Rather than making a simple case-based payment, DRGs take a variety of different risk factors into account like the patient’s age or blood pressure. If additional risks are found than the price of treatment is increased.

Back in 1992, Australia was the first country to adopt DRG as a nationwide standard for hospital payment. Based on the Australian model, several European countries adapted DRG to address their own healthcare needs. In 2004, Germany started to use what they called D-DRG, or German DRG, and is regarded as having developed the most sophisticated version of this system. China started research on DRG in 2010, and after six years of preparation a working group under the NHFPC created China’s own DRG called the C-DRG. In June 2017, China’s first trial using DRG started in 33 hospitals located in Shenzhen, Sanming (Fujian), Kelamayi (Xinjiang) and three provincial hospitals in Fujian. Based on the results of these trials the DRG may be rolled out nationwide.

Looking at the experience of widespread DRG implementation in Germany the main concern for China adopting a similar model is the massive expansion of bureaucracy it would entail. The D-DRG’s 2018 manual has more than 5,000 pages. Hospitals would need to employ highly qualified personnel just for data entry. Increased supervision would be necessary to guarantee data accuracy and prevent fraud.

In conclusion, there is no perfect solution for hospital payment. Controlling the cost of expenses while at the same time ensuring high-quality medical services is a difficult undertaking. Ultimately, payment system reform needs to go hand-in-hand with other aspects of medical reform. For example, reform of the payment system may incentivise hospitals to shorten the average length of hospitalisation, but this desired outcome should be accompanied by improved home care and discharge management.

Volker Müller, has worked in the Chinese medical industry since 2000 and is co-manager of the Healthcare Equipment Working Group at the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China. His area of focus is in disposable medical devices and healthcare reform in China.

Recent Comments