China’s cybersecurity, data and personal information compliance for EU SMEs

In recent years, China has made significant efforts to strengthen its governance system for cybersecurity, data and personal information (PI) protection. Complementing the 2017 Cybersecurity Law (CSL), the Data Security Law (DSL) and the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) came into effect at the end of 2021, stipulating a series of obligations not only for actors based in China but also for those based overseas that process data or personal information generated in the country. In a recent report on cybersecurity, data and PI compliance, the EU SME Centre focussed in particular on data storage and cross-border data transfer procedures, as well as practical issues and scenarios commonly encountered by European Union (EU) small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This article by Arvid Tilner of the EU SME Centre outlines some of the advice included in that report.

Background and legal framework

In line with the concept of cyber sovereignty, where the Chinese Government has the ultimate authority over domestic cyberspace, China developed and strengthened its governance system for cybersecurity, data and PI protection for any company operating within the territory of China – including foreign enterprises. At the same time, the three main laws have an extraterritorial reach, extending their scope to overseas entities based abroad. Hence, EU SMEs falling under their scope, including those without a legal presence in China, will need to comply with these Chinese laws and the related regulations and standards.

The specific obligations and requirements stipulated by these laws and relevant standards distinguish among different subjects and roles, specifically:

- network operators (NOs): Owners and administrators of networks and network service providers, such as enterprises operating an intranet or an enterprise resource planning system;

- critical information infrastructure (CII) operators: Entities operating important network facilities and information systems in key areas that may endanger national security, the economy, people’s livelihoods or public interest; and

- providers of network products and services: Providers, manufacturers and integrators of network products and services, such as computers and communication equipment, among others.

Foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) operating in China with EU companies as shareholders may fall under the scope of these definitions, though—especially in the case of CII operators—few SMEs are likely to be affected.

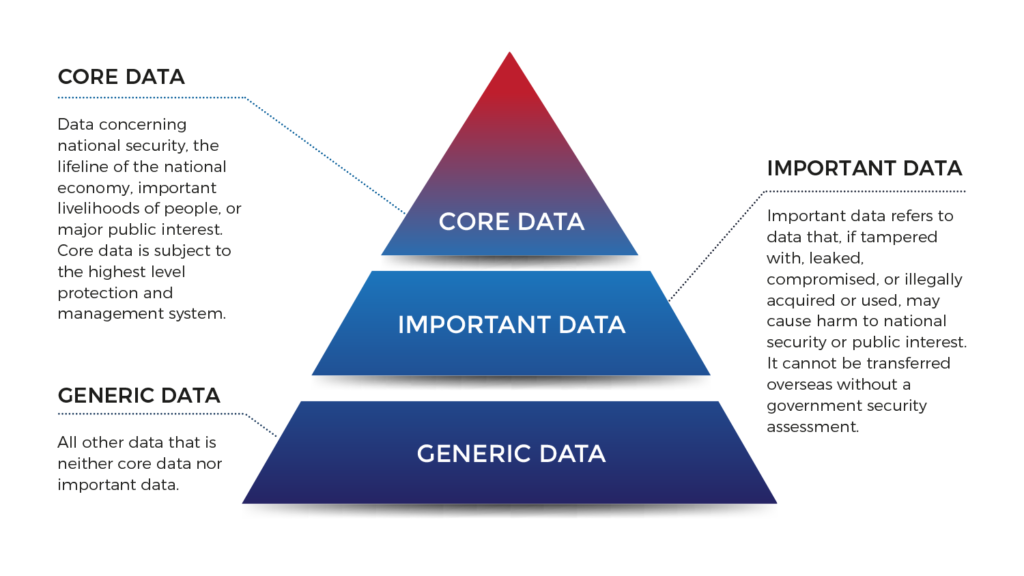

In addition, different definitions, classifications and grades of data and PI are stipulated by the legal framework and require specific levels of security and protection mechanisms implemented by the relevant processors.

Cross-border transfer of data and personal information

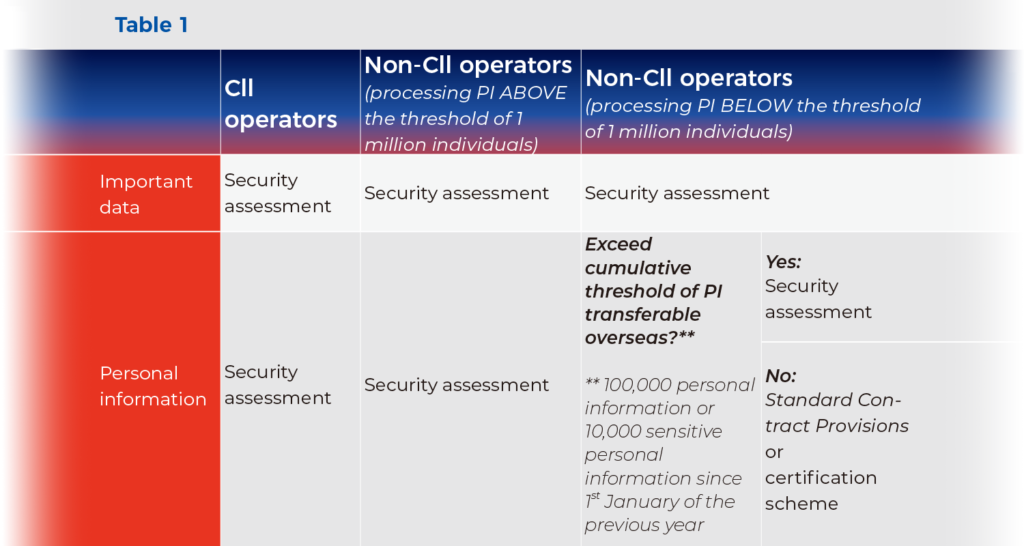

It is essential for FIEs operating in China with EU companies as shareholders to familiarise themselves with the latest specific requirements and procedures for transferring overseas data and PI processed in China, which vary depending on the nature of the processor and the type of data. Table 1 outlines the three legal mechanisms for lawful transfers of data and PI outside of China that have been laid down by law.

Method 1: Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) security assessment

The cross-border transfer of certain data and personal information outside of China requires prior Chinese Government approval through a CAC security assessment for:

- any entity transferring important data from China overseas;

- CII operators, as well as non-CII operators transferring personal information above the threshold of one million individuals; and/or

- any entity transferring important data or a cumulative amount (counted from 1st January of the previous year) of PI of more than 100,000 individuals, or sensitive PI of more than 10,000 individuals.

After conducting a self-assessment evaluating the risks involved in the transfer, the applicant needs to undergo a formal security assessment conducted by the CAC. This will be carried out within 45 working days—or even more in complex cases—and will focus on seven key targets, such as the purpose, scope and method of data transfer, the impact of the legal environment of the receiver’s country on the security of the data, and the alignment of the receiver’s protection level with Chinese laws and regulations. Afterwards, the applicant is formally notified on whether a re-examination will be necessary or if approval to sign the relevant contract and begin the cross-border transfer process has been granted.

Method 2: Standard Contract Provisions

In circumstances where a security assessment prior to cross-border data transfer is not mandatory, PI exporters that process PI should follow the Standard Contract Provisions issued by the CAC. At the time of writing, only draft versions of the specific requirements and obligations have been made available, but they imply that eligible PI processors must first conduct a PI protection impact assessment. This risk self-assessment seems to follow the same six elements that are required for the CAC security assessment. In addition, the contract signed with the overseas receiver must follow six standard provisions, or, ideally, the standard template provided by the CAC can be used. Within 10 days of the enforcement date of the contract, the PI exporter must file the results of the impact assessment and a copy of the signed contract with their local CAC.

Method 3: Certification scheme

As an alternative to the Standard Contract Provisions, non-CII operators processing PI below the threshold of one million individuals may choose to apply for certification for a cross-border transfer of personal information. Specifically, certification can be obtained for:

- cross-border transfer of PI between subsidiaries and affiliated companies of multinational companies or other economic organisations; and

- PI processing activities that are subject to the PIPL’s extraterritorial reach.

The application for certification can be submitted by the China-based subsidiary, which acts as the PI exporter, or by a designated agent in China for foreign companies subject to the PIPL’s extraterritorial clause. The certification process focusses on both the PI processor acting as the exporter and the offshore PI receiver, and usually reviews four key elements: (i) the legally-binding agreement signed by both parties; (ii) the two parties’ compliance in appointing a responsible officer and setting up relevant departments; (iii) their abidance with the same PI cross-border processing rules; and (iv) a PI security impact assessment that must be carried out before the data transfer. No list of designated certification bodies has been released as of September 2022, and further uncertainties remain. This method of cross-border PI transfer is therefore currently not an option for SMEs.

Compliance tips for EU SMEs

The new governance framework for cybersecurity, data security and PI protection brings a paradigm shift in the way EU companies have been operating their businesses in China. Depending on their specific business, market share, risk tolerance and integration within the Chinese ecosystem, as well as the level of integration of their China-based activities into global value chains, EU SMEs may face many changes and uncertainties regarding compliance with the CSL, DSL and PIPL. Violating the obligations and requirements of cybersecurity, data and PI protection may trigger administrative, civil or even criminal liabilities – depending on the specific circumstances and the impact on the rights of China’s citizens, organisations, public interest and national security. Hence, a series of actions must be taken to ensure EU SMEs’ compliance and to prevent disruptions to their businesses in China:

- Conducting data mapping of all data and PI processing activities done in China and the extraterritorial reach. This mapping should clearly identify the amount and extent of outbound flows of such data and PI, as well as the nature of companies’ relationships with their Chinese partners.

- Identification of requirements and security measures based on the purpose, nature and amount of data and PI flows resulting from the mapping. This data assessment should also clearly identify any data flows at risk of non-compliance for future development.

- Establishing a sound emergency plan targeting different scenarios in the case of incidents such as network attacks or data breaches.

- Review all current contracts/policies with Chinese partners and even employees to see if they are aligned with the relevant provisions and inform about changes and integrate amendments.

- Regularly train personnel involved in data flows both in China and at company headquarters in Europeon cybersecurity and data protection policies.

Note: This article is based on the report Cybersecurity, Data and Personal Information Compliance for EU SMEs in China by the EU SME Centre, available to download from their website, www.eusmecentre.org.cn.

The EU SME Centre is a non-profit initiative funded under the European Union’s Single Market Programme (SMP). The EU SME Centre provides a comprehensive range of hands-on support services to European SMEs, assisting them to establish, develop and maintain commercial activities in the Chinese market. By offering support through the provision of information, confidential advice, networking events and training, the Centre focusses on the crucial early stages of SMEs’ market penetration strategy. The Centre also acts as a platform facilitating coordination amongst European Member State and public and private sector service providers to EU SMEs.

Recent Comments