Modernisation with Chinese Characteristics

China is undergoing a historically significant transformation in its manufacturing sector. However, by driving industrial policy with the forceful hand of the State, Made in China 2025 runs the risk of patching old problems with new ones. Amid growing voices of concern, David Maurizot, Greater China director at Advention Business Partners, explains what implications this development will have for both European businesses and the broader Chinese economy.

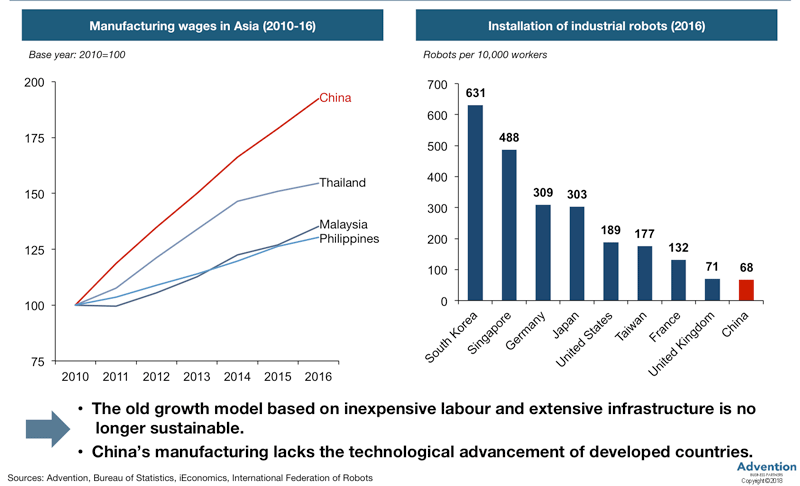

China is at a crossroads. After four decades of unbridled economic growth it is now finally time for the country to be treated as a political superpower. However, balancing political aspirations with their economic agenda is proving to be a challenge for Chinese leaders. Currently the country faces an aging population and rising labour costs, which makes the old economic model based on inexpensive labour and infrastructure expansion unsustainable.

How has Beijing responded to this balancing act? They have responded by blending timeworn soviet-style centralised planning with modern manufacturing ambitions that echo Germany’s Industry 4.0 initiative. This combination has resulted in an ambitious masterplan titled Made in China 2025. The initiative’s goal is to make China the leading global manufacturer in the coming decades—in time for the centenary of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 2049—and transition the country from relying primarily on low value-added products to high-tech goods and advanced manufacturing. This shift includes a new focus on industries ranging from robotics, new energy vehicles and aviation to information technology.

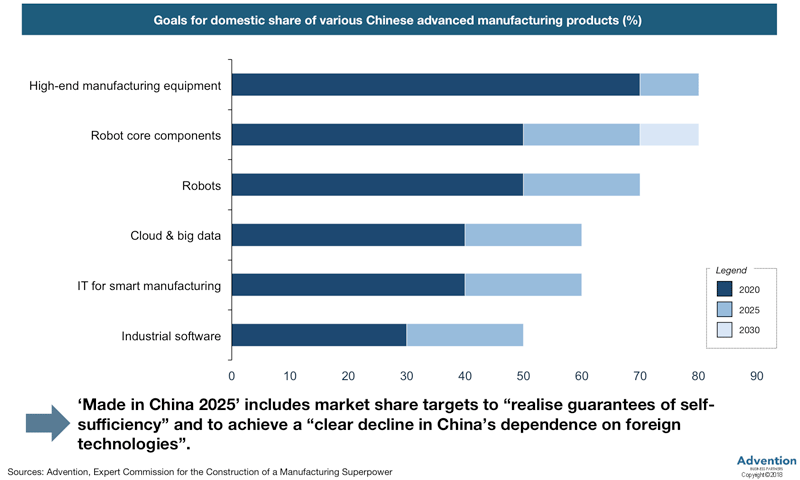

Reflecting the enormity of this transformation, the plan’s quantitative objectives are characteristically ambitious in both its breadth and the time given to reach them. True to form, the heavy hand of the State is visible everywhere as targeted industries will be supported with subsidies, low-interest loans and tax breaks.

Staring down the barrel of potentially seismic shifts in the manufacturing industry, not only in China but all over the world, it must be asked: where do foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) operating in China stand on this initiative and can they benefit from this massive economic intervention?

What is Beijing’s rationale?

The old manufacturing industry is currently being squeezed by cheaper wages in developing economies, while being outpaced by technology-driven efficiency gains in developed countries. The central government is concerned that, in the absence of a major upgrade, the domestic manufacturing sector risks having uncompetitive pricing and unsophisticated product offerings.

To avoid the middle-income trap and fulfil its ambition to become an advanced manufacturing superpower, China must transition into industries now dominated by developed economies. However, the country currently lags far behind its competitors and centrally-planned incentives including subsidies and other forms of market protection are being provided to domestic enterprises to drive the whole manufacturing sector in the desired direction.

Opportunities exist for FIEs in the short term

This sweeping transition, despite emphasising Chinese technological independence, presents a range of opportunities for European firms that are capable of aligning themselves with China’s policy objectives. European firms possess extensive experience in moving production up the value chain and in doing so have refined skills in innovation, standardisation, productivity and supply-chain integration, with each being central to implementing the Made in China 2025 initiative. While there is certainly heightened competition from Chinese companies and a push to buy local, benefits stand to be had by those European companies that can form strategic partnerships with Chinese companies and provide needed critical components, technology and management skills. Doing so should result in select European firms taking a modest share of China’s economic pie, all while riding the coattails of Chinese industries that are experiencing accelerated growth.

Domestic firms will replace foreign firms

While short-term benefits may exist, policymakers have made it clear that China aims to eventually replace foreign technology with domestic competitors and groom national champions that can compete in global markets. The State Council’s original notification on Made in China 2025 included market share targets for China to “realise guarantees of self-sufficiency” for 70 per cent of their “basic core components and important basic materials” by 2025. This also meant the country had to achieve a “clear decline in China’s dependence on foreign technologies”.

With such clear autarkic ambitions for the long term, FIEs in China are expected to continue playing on an uneven field.

Operating conditions for FIEs in China will become increasingly difficult

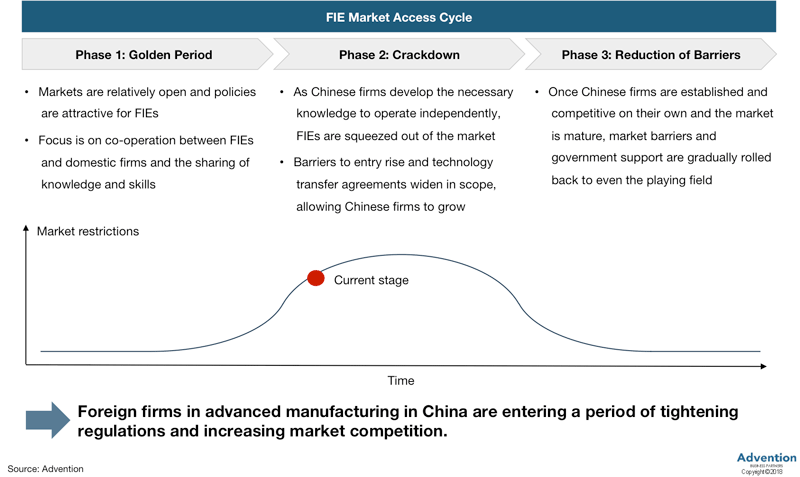

One way China will achieve this shift towards domestic dominance is by increasing the barriers to FIEs entering and operating in the country. As observed on multiple occasions, Chinese regulators obediently follow strategic policy objectives in a largely predictable fashion. Domestic markets are initially open to foreign technology and outside investment, however, once Chinese companies have made significant progress in bridging the technology gap, policymakers systematically intervene to increase domestic market share by erecting barriers to foreign competition.

After a period of relative openness, European firms operating in the key sectors found in Made in China 2025 are now feeling the pinch of tightening regulations and market access.

China’s leaders understand that China is lagging behind in key sectors and hence are pursuing a strategy of forced technology transfers. While this is nothing new for FIEs, there has recently been a push for even more advanced, proprietary technologies to be shared before entering the market. Conditions are also tightening for firms already operating China, with over half of European firms in the automotive and machinery sector reporting business becoming more difficult in 2017. Meanwhile, one quarter of European firms in the machinery and aerospace sectors were required to transfer advanced technology to maintain market access. Such forced technology transfers not only run contrary to rhetoric on increased market openness, but also threaten the long-term competitive advantage enjoyed by European firms.

Outbound technology acquisitions threaten competitive advantage

In contrast to the more domestically-focused initiatives of the past, China is increasingly looking to cross-border investment for acquiring the cutting-edge technology needed to advance policy objectives. Over the course of the past three years there has been an unprecedented wave of outbound investments into European firms that hold relevance to Made in China 2025. In itself, this is neither surprising nor objectionable. However, many of these investments have been in areas where European businesses are unable to make equivalent investments in China. These investments are often backed by a complex and opaque network of companies that disguise the government’s guiding role and undermine the principle of fair competition.

Who is most at risk?

Made in China 2025 will have an impact not just domestically but abroad as well, with select countries feeling the effects of this ambitious policy more than others. In particular, countries with high-tech industries that specialise in manufacturing will be exposed to the wider effects of Made in China 2025. Within Europe, the nations expected to be impacted the most include Germany, Hungary, Ireland and the Czech Republic, which each generate more than 50 per cent of their manufacturing output from high-tech industries. China’s industrial policy will invariably alter the competitive landscape of these industrial economies.

Long-term implications of overcapacity and an unbalanced economy

Reflecting on contemporary examples where the government has provided incentives to promote industrial development, it is not unreasonable to expect that the problem of overcapacity may arise. A fixation on quantitative targets and the inefficient allocation of funding may diminish Made in China 2025’s impact, with overeager provincial governments pursuing ambitious projects that result in excess aggregate supply.

As overcapacity depresses profit margins in the short term, Chinese firms with access to subsidies and favourable funding conditions may make incremental gains towards bridging the technology gap. However, in the long term, as previously seen in the steel and aluminium sectors, government-led misallocation of resources will result in significant costs that will be felt throughout the global economy.

Greater emphasis should be placed on reciprocity and market forces

There is no doubt that China’s attempts to encourage its domestic industries in higher value-added manufacturing have a great deal of merit. However, the broad set of policy tools being employed to facilitate Made in China 2025 are highly problematic. In the face of this new challenge, European industrial firms and European Union authorities must reconcile short-term benefits to be gained from accessing China’s growing market with the legitimate need to prevent the erosion of their long-term competitive advantage. To ensure not only that China reaches its full technological potential but that Europe enjoys a competitive business environment, China should employ a domestic industrial policy that is focused on market-led decision-making, greater reciprocity and a collaborative ecosystem that fosters innovation. These tactics should be used, rather than the current dose of heavy economic interventionism that has proven problematic not only in recent years, but since the beginning of the People’s Republic of China.

David Maurizot is the China director of Advention Business Partners, a European-based strategic advisory firm, and a board member of the French Chamber of Commerce in China. A fluent speaker of Mandarin Chinese, he has provided strategic advice to European companies (financial investors, MNCs and SMEs) in China for more than a decade. David also serves as the vice chair of the European Union Chamber of Commerce’s Investment Working Group in Shanghai.

Recent Comments