China’s new online publishing regulations

China’s State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) recently issued their new, joint Regulations on the Administration of Network Publication Services (Regulations). They overhaul the previous regulations—which took effect in 2001—significantly tightening applicable legislation. It reaffirms that foreign publishers are prohibited from the online publishing market and further restricts the operations of Chinese online publishers. Deanna Wong of Hogan Lovells summarises the key points of the Regulations, which came into effect on 10th March.

China’s State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) recently issued their new, joint Regulations on the Administration of Network Publication Services (Regulations). They overhaul the previous regulations—which took effect in 2001—significantly tightening applicable legislation. It reaffirms that foreign publishers are prohibited from the online publishing market and further restricts the operations of Chinese online publishers. Deanna Wong of Hogan Lovells summarises the key points of the Regulations, which came into effect on 10th March.

Wide Scope

The Regulations have a very large scope of application. They define online publication services as “the provision of online publications to the public through the information network”. This definition, if applied strictly, could in theory encompass virtually any uploading activity on the Internet by both individuals and businesses in China. However, the Regulations also provide that the “specific classification” of online publication businesses “are to be further clarified” by the authorities. It is anticipated—and, in fact, the SARFT informally confirmed—that the scope of the Regulations will be limited to professional online publishers, excluding individuals and entities that only occasionally or incidentally publish online media in China.

As to the types of media covered by the Regulations, the following three—very broad—categories of online publications are listed under Article 2:

- Works of literature, art, science and technology, including literary works, pictures, maps, videogames, animation, audio, video and audio-visual works.

- Digitised books, newspapers, magazines, sound and/or video recordings and electronic publications that were previously published via other media.

- Online databases of digital works developed from the selection, edition and collection of the above two types of works.

Additionally, a catch-all section is provided, allowing the SARFT to add other types of media to the scope of the Regulations, e.g. to include novel types of digital works and arguably content aggregators.

Publication licences required

Any individual or entity providing online publications to the public in China must apply for an online publication service licence with the SARFT. Such licences must be obtained before the entity can engage in any online publishing in China, and will be valid for five years.

Applicants must, among other things, fulfil the following requirements in order to be eligible for a licence:

- The servers that online publications are stored on must be located in China.

- The legal representative of the applicant must be a Chinese citizen residing in China.

- The applicant must establish a system for self-editing/scrutiny (this provision is somewhat unclear, but is probably directed at any ‘sensitive’ content).

Licences are non-transferable (this includes ‘sub-licensing’, leasing etc.) and information regarding the licence, such as the licence number, must be clearly displayed on the publisher’s home page.

Anyone providing online publications to the public in China without a valid licence faces administrative penalties, such as removal of the website, including all online publications, confiscation of illegal proceeds and fines of five to 10 times the amount of the illegal turnover, and even criminal sanctions.

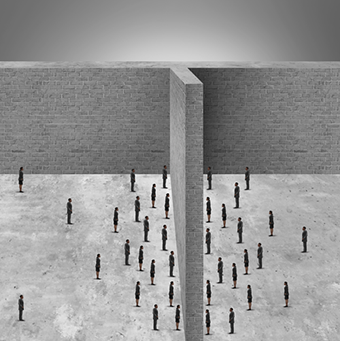

Foreign entities banned

Foreign entities, including Sino-foreign joint ventures and WOFEs, are banned from providing online publications to the public in China, and are not eligible for a publication licence. Sino-foreign publishing ‘cooperation programmes’ may, on the other hand, be permissible, but remain subject to the SARFT’s prior and ad hoc approval, an amendment that is a noted tightening compared to the standard ‘prior security report’ used in the 2012 draft Regulations.

However, this seemingly draconic measure does not come as a real surprise since foreign entities were already banned from investing in the online publication sector in China under the current (2015) version of the Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign Investment Industries.

It is currently unclear if foreign media companies with overseas servers will be targeted or whether the Regulations are just targeted at content providers in China.

Increased government control over online publishers

The Regulations provide that online publishers must conduct their business with respect for China’s laws and regulations, China’s socialist direction and China’s socialist core values. Online publishers will need to report annually to the local authorities about their operations, the quality of their publications and their compliance with the laws and regulations, among others. The local SARFT authorities are also granted powers of inspection.

If an online publisher is suspected of violating the publishing laws and regulations, committing copyright infringement or other illegal conduct, the local SARFT authorities can suspend its operations for up to 180 days, pending further investigations. The online publisher must then cease all publishing activities for the time of the suspension.

Monitoring obligations for ISPs

Monitoring obligations for ISPs

The Regulations impose a direct duty of verification on Internet Service Providers (ISPs) for so-called acts of “active intervention”. This means that they are obligated to verify such information as online publication licences and the business scopes of online publishers when providing services such as search engine result ranking, advertising and promotion. Any ISP failing to do so faces fines of up to CNY 30,000.

Specific rules for online games and minors

Foreign online video game developers are required to license their software copyrights to a Chinese online publishing licence-holder, since only such licence-holders are permitted to publish content online in China. This domestic Chinese licence holder will then have to apply for a pre-approval from the local SARFT authority before a game can be published/uploaded on the Internet in China. This pre-approval is a requirement for both foreign and domestic games developers.

The Regulations also provide for specific measures to protect minors. In particular, they prohibit the online publication of:

- Content encouraging minors to imitate immoral or criminal conduct;

- Content that is deemed horrific, cruel or likely to prejudice the physical or mental health of minors; and

- Content that violates the privacy of minors.

Conclusion

The Regulations are the last in a series of laws that significantly tighten regulation of the Internet and the freedom of operation of technology companies in China.

The objective—underlined by President Xi Jingping in his keynote speech at the World Internet Conference in Wuzhen in 2015—is to make the Chinese Internet, and IT in general, more “secure and controllable”. This has been reflected in the recent National Security Law, the Counter-Terrorism Law and a draft of the Cyber Security Law, among others. The result is often the exclusion of foreign players and content providers as they are considered less “secure and controllable”.

However, the clear tightening of China’s Internet and technology legislation notwithstanding, the Regulations do leave some loopholes for foreign content providers (e.g. Sino-foreign cooperation programmes) and for Chinese publishers to publish their media in China. This should allow market players to continue targeting China’s immense online population—estimated at 700 million people—provided they tread carefully and stay within the boundaries of the government’s laws, regulations and policies.

As of now, the Regulations seem incomplete and require further clarification from the authorities. For example, more details are needed about the application process for licences and the application for permission for Sino-foreign cooperation projects, and the specific classifications of online publishers are currently still lacking.

We will be providing a more comprehensive article on our website, and will continue to keep you updated with further developments as soon as they become available.

Hogan Lovells is a global legal practice with over 2,800 lawyers in more than 40 offices including three offices in Greater China, five offices in the rest of Asia and 17 offices in Europe. The Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong offices provide a full range of services covering antitrust/completion law, intellectual property, media and technology, banking and finance, corporate and contracts, dispute resolution, government and regulatory, projects, engineering and construction, real estate, and restructuring and insolvency.

Recent Comments