The 18th Party Congress and leadership succession has been heavily scrutinised by business and political analysts looking for clues as to what may happen next. Alistair Nicholas and Qu Hong from Weber Shandwick produced a recent study entitled China at the Crossroads: Power Politics and Transition at the 18th Party Congress, which takes a close look at the new appointments in an attempt to extrapolate indicators of future change in Chinese politics, the economy and general business landscape. What follows is an executive summary of their report.

A once-in-a-decade leadership change meant that Xi Jinping has taken the reins of the Communist Party in a China very different to that inherited by his predecessor 10 years ago. When Hu Jintao became the Party General Secretary, China was the world’s sixth largest economy; today it is the second largest. Then, it barely had a ‘green water’ navy capability; today it is an aspiring ‘blue water’ force capable of projecting its power as far as the Mediterranean. It recently put ‘taikonauts’ in orbit and has plans to plant the Chinese flag on the moon.

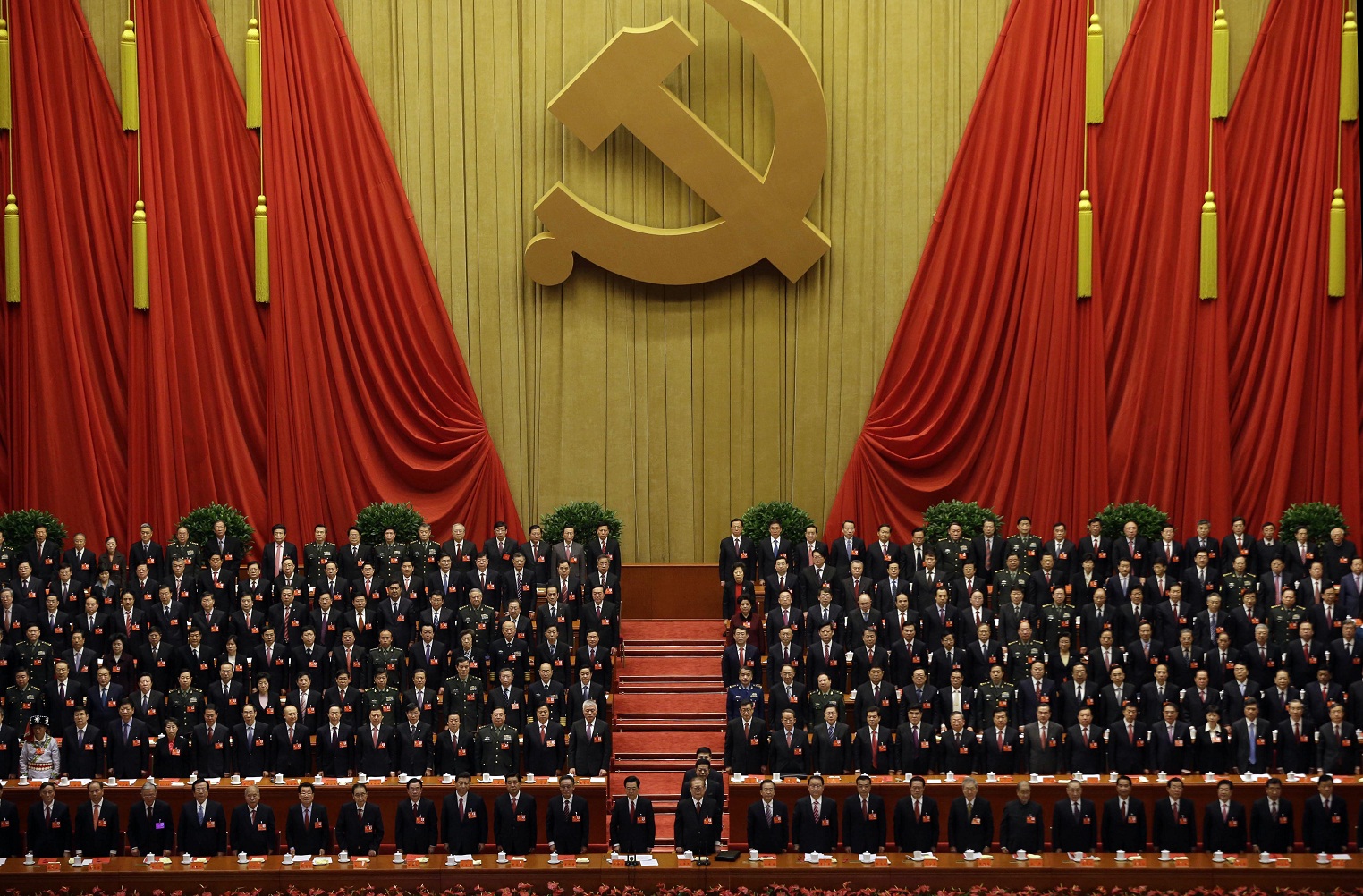

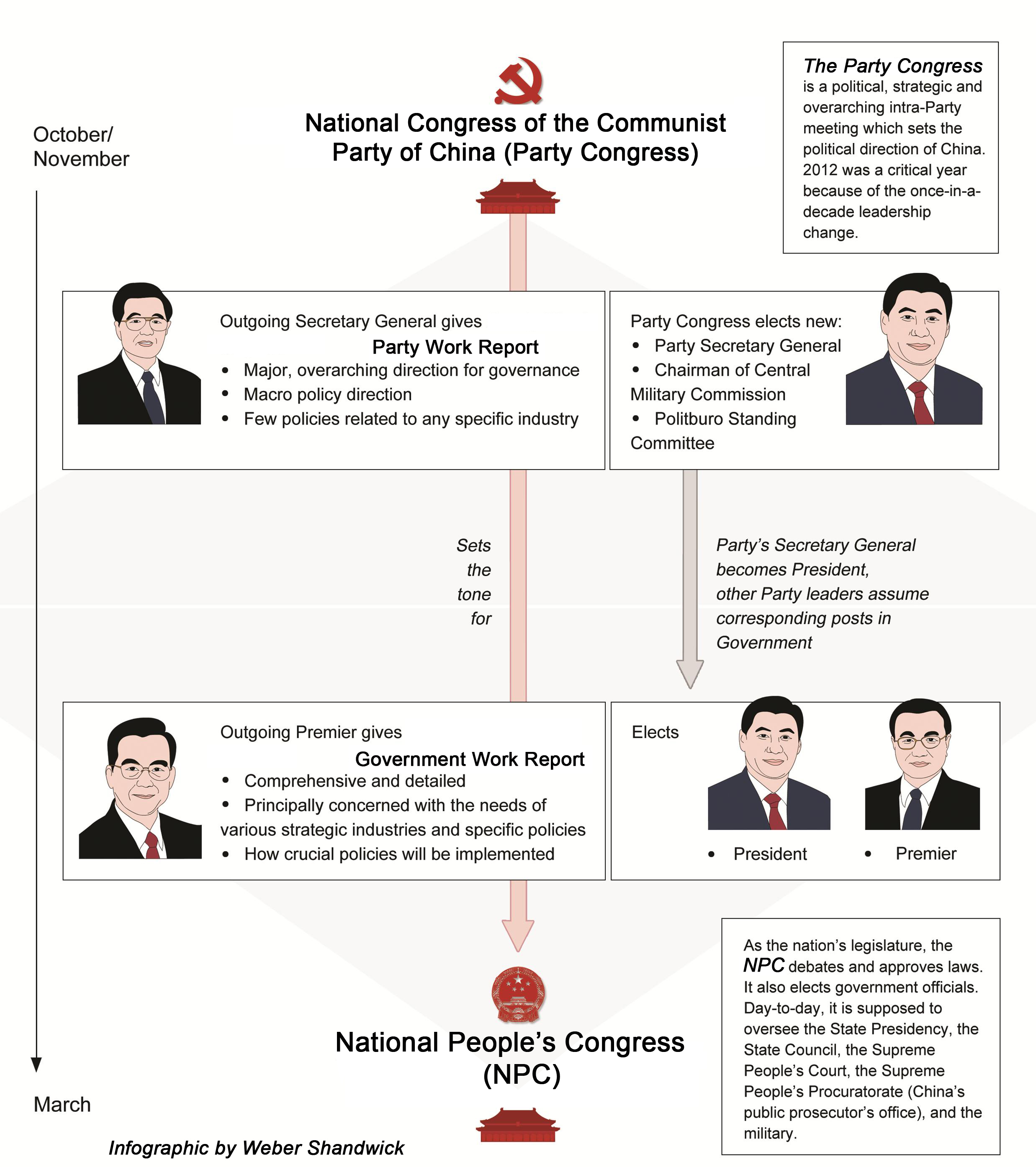

China-watchers and pundits were eager for substantive declarations during the weeklong Communist Party Congress in November, where Xi made his first remarks as General Secretary of the Communist Party. However, many failed to note that this was the first stop along a journey—a party convention before the official transition of China’s presidency at the National People’s Congress next March.

Unlike the West, in which political power is amassed by newly elected leaders publically, who spend it in haste, in China, it is accumulated slowly behind closed doors over a lifetime. That helps explain how 86-year-old former President Jiang Zemin secured important posts for his protégés this year.

In this light, media expectations were arguably unrealistic for insights from a single Party gathering. Foreign publications asked bold questions about what China’s new leadership would do with their hands now on the levers. But sudden sweeping reforms were unlikely in a Party that rules more by (sometimes mysterious) and very tentative consensus and power-brokering. This was even more apparent than usual given recent embarrassments, notably the fall from grace of one of its senior apparatchiks, Bo Xilai (now expelled from the Party and possibly facing charges of corruption, in the wake of his wife’s conviction for murdering her British business partner).

In a country where action is much more meaningful than words, writing off the likelihood of reform in the first week of a ten-year administration betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of how things work in China.

While many questions remain unanswered, a few suggestions did emerge:

Xi appeared confident and collected, with the six other members of the newly-appointed Politburo Standing Committee alongside him. Two reformers touted as possible choices for the Committee were not present, which may suggest the Party’s reluctance to promote too obvious brands of change within its ranks, or at least to do so in the first year of a new administration.

In the meantime, the seven-member Standing Committee of the Politburo will take key ministerial positions when the National People’s Congress convenes in March, with quite a major task ahead of them.

Mr Xi’s Inbox

Xi will formally be installed as the country’s president, and is expected to address issues such as intellectual property and food safety, energy policies and lending practices of state banks. The economy will top the agenda, given the global economy, slumping foreign investment in China and the slowing of the country’s manufacturing exports.

China’s maturing economy will need to rebalance to a consumer-based economy, requiring significant reforms of the state owned enterprises (SOEs) and the banking system. Some observers believe that monopolies need to be broken for the private sector to move forward and the power of consumer savings to be unleashed.

Leaders will also need to address economic disparities: there appears to be a widening gap between the rich and poor. To that end, outgoing Party Chairman Hu Jintao called for a doubling of GDP and per capita income by 2020—no mean challenge for Chairman Xi. Hu didn’t provide plans on how to achieve these goals (at least not publicly), or how to do so in a way that will achieve a more equitable distribution of national wealth.

Hu’s contribution to the Party’s theoretical framework was enshrined as ‘Scientific Development’, following in the tradition of successive generational themes: Marxist-Leninist Thought, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Thought, and Jiang Zemin’s ‘Three Represents’. For Xi, ‘Hu Thought’ will require balancing developmental needs with sustainable growth and equitable wealth distribution to achieve Hu’s objective of a ‘harmonious society’.

Despite calls for political reform by outgoing Premier Wen Jiabao, Hu, in his report to the Party Congress, focussed more narrowly with a call to address corruption which, it is feared, might undermine the Party’s authority. This theme was echoed by Xi in his speech to delegates. But neither Hu nor Xi addressed the judicial reforms, which some believe are needed to bring corrupt officials to book. The question of broadening democracy within the Party was also not addressed yet although there was a proposal to allow delegates to table motions collectively.

Of growing importance is how China can progress foreign policy objectives, from asserting the rights of the developing world on environmental issues to securing resources and protecting important sea-lanes, to territorial disputes. China’s rise, compounded by nationalist sentiment, means Xi will likely be pressured to be more assertive internationally.

State of Play

Much of what happens will depend on private deals and behind-the-scenes political discussion. Party members compete for power, influence and control. They do not necessarily share a uniform ideology, political association, socio-economic background or policy preference any more than their counterparts in the West. This can foster lively debate behind the scenes.

Much will depend on how Xi persuades and marshals support. But one important sign came with the transfer of the Chairmanship of the Central Military Commission to him by Hu Jintao. By relinquishing this position now, Hu has established Xi as China’s paramount leader and earned himself credit for what may be seen as a selfless action on behalf of the Party. This may ease tensions between the factions and establish an environment for Xi to push forward important reforms. It now remains to be seen whether and how Xi will rise to the challenge.

Alistair Nicholas is Executive Vice President Asia at Weber Shandwick and heads up the Corporate & Public Affairs Practice of the firm for the region. Qu Hong is Chief Government Affairs Consultant for the firm in China. This article is based on the firm’s analysis of the leadership transition at the 18th Communist Party of China Congress held in Beijing in November. To receive a copy of Weber Shandwick’s full report please contact aruan@webershandwick.com.

Recent Comments