Progress in China’s capital markets is far from satisfactory, falling well short of China’s economic developmental needs, the expectations of policy designers and indeed the market itself. In the following article Chen Xingdong, Chief Economist for BNP Paribas (China) Ltd, examines the current situation and finds that although it currently bears no comparison with the sophisticated markets in the west, the desire for radical development — both from investors and the general demand for capital raising — means China’s capital markets have enormous potential.

After 30 consecutive years of rapid growth, increased affluence amongst many Chinese has created a demand for financial asset or wealth management, particularly amongst those in the top 10-20 per cent of China’s wealthiest citizens. Under current conditions China’s underdeveloped capital markets has given rise to a distortion of capital allocation and damaged capital efficiency, and has also driven bubbling for certain classes of assets. From our perspective, with the new Chinese leaders committed to a fresh round of reforms, we believe that bold restructuring of the financial system, and specifically capital market development, will be one of the fundamental reform programmes undertaken.

After 30 consecutive years of rapid growth, increased affluence amongst many Chinese has created a demand for financial asset or wealth management, particularly amongst those in the top 10-20 per cent of China’s wealthiest citizens. Under current conditions China’s underdeveloped capital markets has given rise to a distortion of capital allocation and damaged capital efficiency, and has also driven bubbling for certain classes of assets. From our perspective, with the new Chinese leaders committed to a fresh round of reforms, we believe that bold restructuring of the financial system, and specifically capital market development, will be one of the fundamental reform programmes undertaken.

An underdeveloped market

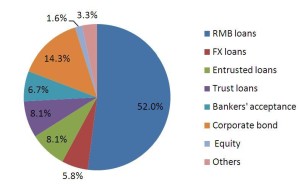

It may be easier to understand the current situation of China’s capital markets in the context of corporate capital raising — known as direct financing when raised through capital markets, or indirect financing when raised through commercial banks. Even after more than two decades of development of the capital markets (equities market), indirect financing remains in a dominant position. Bank loans (including renminbi and foreign exchange loans) made up 57.8 per cent of total social financing in 2012, with the bond market accounting for 14.3 per cent and the equity market taking a mere 1.6 per cent.

Comparison of international equity market cap as of 10th April, 2013

Source: CEIC

Please click for larger image

Although we must take into account the different stages of economic development in each country, figure two (left) illustrates a stark comparison. Equity market cap against GDP in China stands at just 37.4 per cent, compared to 142.4 per cent in UK, 120 percent in the US, and is even lower than India which is 59.3 per cent. China is already the second largest economy in the world and its GDP is some 53 per cent of that of the US, yet its equity market cap is only 16.4 per cent of the US.

By contrast, China’s financial market has been over monetised. Broad money supply (M2) in China rapidly expanded from RMB 18.5 trillion in 2002 to RMB 97.4 trillion in 2012. Over this ten-year period, broad money supply increased 4.3 fold, growing by 18.2 per cent in compound annual growth rate (CAGR), compared to 10.4 per cent in CAGR in real GDP growth or 15.7 per cent in CAGR in nominal GDP growth. Broad money against GDP increased to 187 per cent in 2012. Over monetisation distorts capital distribution, reduces capital efficiency, and causes deterioration in capital equity.

Poor performance

China’s A-share market performance has been disappointing. If we take January 2008 as the base of 100, the China A-share market, represented by the Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index (SHCOMP), is the poorest performing market when compared to the S&P 500, MSCI Emerging Market, Euro STOXX, and even the HSCEI (trading in the so-called H-share — shares of companies incorporated in Mainland China and traded on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange).

Comparison of international equities stock market performance as of 3rd May, 2013

Source: Wind Financial

Please click for larger image

China’s GDP in 2012 was 42 per cent higher than that of 2008 in real terms, or 65 per cent higher in nominal terms. Over the same period the US only increased 3 per cent, while the EU’s economy is currently at a level below 2008. This indicates that China’s poor performance has nothing to do with economic fundamentals; rather it can mainly be attributed to irrational market fundamentals, poor legal framework and enforcement, poor investor protection and lack of effective government oversight.

Bond market gained strength

In contrast, the credit bond market in China has performed extraordinarily well since last year. Though total bonds (including treasury bonds, financial bonds, PBOC bills, corporate bonds) issued rose by only 3.5 per cent to RMB 8.1 trillion, generic credit bonds, covering enterprises bonds, corporate bonds, medium-term notes and short-term financing bills surged 44.6 per cent to RMB 3.6 trillion. Local government financing vehicle (LGFV) bonds were particularly strong, with an issuing amount of RMB 892.8 billion, more than double the RMB 371.5 billion issued in 2011.

The bond market has become an increasingly important funding channel for corporate and local government. Net financing via the bond market reached RMB 2.25 trillion last year, soaring by 64.7 per cent, and accounting for 14.3 per cent of total social financing of RMB 15.8 trillion, compared to 10.6 per cent in 2011.

This encouraging development in direct financing is exactly what policymakers have been hoping to cultivate for many years; however, the flourishing bond market has its latent problems as well.

The key problem for the bond market is market segmentation due to political and administrative reasons. It is artificially divided into the platform of stock exchanges in Shanghai and Shenzhen under CSRC regulations, the interbank market under People’s Bank of China (PBOC) regulations and large corporate bonds issued through general financial institutions under the administration of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). In the absence of an integrated system the different bonds markets can result in competition, conflicts and inconsistency.

Furthermore, the bond market is over protected. The government—mainly local—and financial institutions implicitly provide ultimate guarantee of repayment. No defaults have yet taken place, which is an anomaly for a healthy market. The anticipated default of Hailong and LDK Solar last year failed to transpire as they were bailed out by local governments at the last minute. This kind of artificial suppression of credit risk will inevitably lead to a systemic underestimation of risks. Meanwhile, the ambiguous status of LGFV bonds—issued by a corporate in name but backed by local government—is another source of risks in the bond market.

Great potential

Taking the equities stock market as an example, by 2012, there were only 1400 LISCOs (listed companies) in the Shanghai and Shenzhen bourses and 700 SMEs listed in the Shenzhen Stock Exchange.

One thousand companies traded in over-the-counter (OTC) trades—trades done directly between two parties without supervision of an exchange—and China has just started to develop the so-called Third Board exchange (an OTC market for growth enterprises), with the first one being set up in Beijing in the second half of 2012.

But China has in the region of 13 million companies, and it is almost beyond comprehension how many of these are demanding capital raising each year—it is reported there are at least 800 companies queuing up for IPOs right now, all urgently looking for equity capital even under the current bearish market conditions.

At the same time, as the population becomes increasingly prosperous due to the 30-year period of sustained, rapid growth, living standards have moved beyond subsistence conditions and many Chinese are becoming increasingly strong savers. The demand for wealth management is enormous.

The situation of China’s underdeveloped capital markets and its great potential for expansion can be illustrated with the following comparison. The governor of the People’s Bank of China, Zhou Xiaochuan, recently highlighted the underdevelopment of financial and capital markets in China by referring to an IMF study.

It’s reported that in 2011 the ratio of aggregate financial assets against GDP reached a global average high of 366 per cent: 424 per cent in the US; 449 per cent in the Eurozone; 784 per cent in the UK; 540 per cent in Japan; 544 per cent in the “Four Asian Tigers”(Singapore, Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong); but only 303 per cent in China.

It suggests that China’s financial markets lagged 30 per cent behind where they should have developed in line with its economic size and development. It also clearly emphasises the contradictory nature of China’s capital markets, as its broad money M2 ratio to GDP reached a high of 187 per cent by 2012, the highest in the world.

We believe that the new leaders are committed to the bold reforms required to develop China’s capital markets, and that these reforms, as a key part of a larger reform programme, which is under formulation, would become policy in the autumn of this year.

The opening up of capital markets and the participation of foreign companies in its development will be a key element in China, and will prove to be even more important going forward. Financial opening up has so far been much less than anticipated when China entered the WTO in 2001.

It is estimated that current foreign investment made up less than two per cent aggregate of outstanding financial assets in China by 2012. Ten years ago analysts expected the ratio to have reached 20 per cent by now. With the understanding that, on average, foreign financial assets make up 16-35 per cent of domestic aggregate financial assets in the world, the former CSRC Chairman, Guo Shuqing, believed the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) quota can be expanded by nine to 10 times (QFII quota is USD 80 billion, RQFII is RMB 270 billion at this point), and called for an acceleration in the opening of China’s capital markets.

With 475 staff in China, BNP Paribas provides banking, financing and advisory services via its Corporate & Investment Banking and Investment Solutions divisions. Through other vehicles in China, the Bank is also engaged in corporate advisory, overseas equity fund raising and retail banking activities. With both RMB and foreign currency capabilities in China, and leveraging on BNP Paribas’ global platform in APAC, Europe and the Americas, the Bank provides specialised financing solutions to our clients, both in China and overseas.

Recent Comments