Inspiration from private equity managers.

Assets under management of funds that cover Greater China amounted to United States dollars (USD) 624 billion for private equity (PE) and USD 391 billion for venture capital (VC) in 2019.[1] Some of these funds look at cross-border expansion as growth strategies for its portfolio companies. The two key expansion principles explored in this article by Nick Laursen of Laursen van Swieten are based on: first, entering China now not later; and second, entering guided by the ‘China as a venture’ PE methodology.

——————————

Companies should be willing to enter China now, not later, even if the product is still developing, to stay ahead of the competition. Lessons learned along the way can be carried forward into modifying the product though the Chinese market experience.

China as a venture means that companies should see themselves as a venture again when entering the Chinese market. This means starting small, looking closely at the market, being entrepreneurial, adapting constantly, hedging bets, keeping the burn-rate low, and so on. Essentially, it means to act as a young company again that ‘grows up’ in a challenging but rewarding environment.

China is key in the Asian Century (The Why)

The 21st century will be the ‘Asian Century’. Between 2000 and 2017, Asia’s share of global real gross domestic product (GDP) in purchasing power parity terms rose from 32 per cent to 42 per cent, and its share of global consumption from 23 per cent to 28 per cent. By 2040, these two measures are expected to increase further to 52 per cent and 39 percent, respectively.[2]

Within Asia, China is the largest and fastest growing market. This will remain so in the years to come due to strong fundamentals such as science, technology, engineering and math graduates; infrastructure; and industrial value chains. This means that European companies need to be part of China’s growth to be a leading multinational in the 21st century.The investors and companies that build this growth will have a strong influence on 21st century commerce, politics and culture. China’s influence can be seen already as it has a 17.4 per cent share of global GDP. By comparison, the European Union’s (EU’s) share is 15.4 per cent.[3]

China is at the forefront of growth, innovation and change, and, as such, will play a big role in the next phase of globalisation and industrialisation. So, when should European companies consider a China expansion?

China now, not later (The When)

As China grows, it needs new technologies products and services. However, new entrants need to move fast; when foreign entrants finally do expand to China, they soon discover how rapidly their Chinese competitors innovate.

Entering the China market earlier allows more time for successful product localisation and mitigates against being outcompeted by local competition. An early expansion should focus on localising and evolving the product, engaging with local experts and partners, and gaining market feedback quickly.

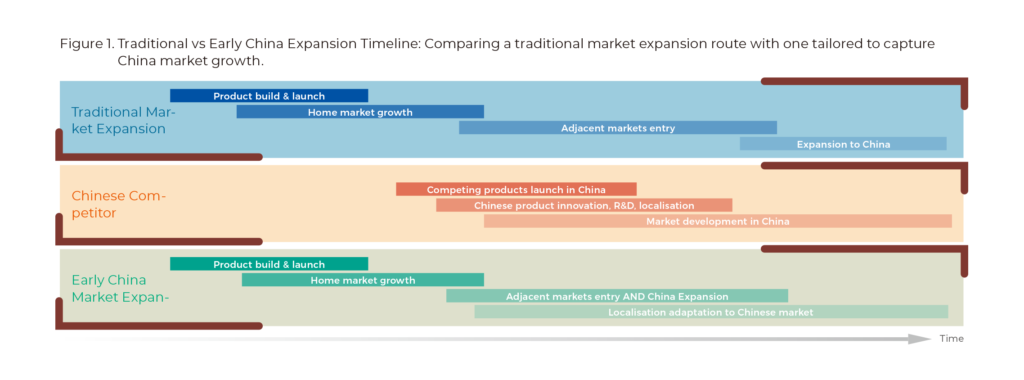

The difference between early and late market entry is best set out in a comparison. Figure 1 illustrates the ‘traditional route’, the ‘Chinese competitor route’ and early China expansion.

European companies should take inspiration from Chinese competitors, which are not afraid to launch products in the germination stage to gain market feedback and inform further iterations. They prioritise learning fast, innovating rapidly and creating good customer experience. Chinese competitors are naturally more familiar with Chinese customers (both business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer(B2C)) and have a more established network. These advantages allow them to operate and establish a product-market fit faster.

European companies should take note of the risks of using the traditional expansion route they take in other markets. Late arrival and poor adaptability to a highly competitive landscape leave many foreign companies at a disadvantage compared to Chinese domestic competitors. Notable examples include Amazon, Google and Uber. These companies all initially gained market share but were eventually overtaken by Taobao, Baidu and Didi, respectively. This shows that even with serious targets and significant financial backing, international entrants can have difficulty succeeding in China.

China as a venture (The How)

The above facts mean that entering China early is vital. However, this early entry puts more pressure on the company when its global structure is still growing and it is unfamiliar with the Chinese market. The answer to this challenge is to see China as a venture and scale up once critical information, network and experience has been obtained. This brings us back to our investment principle.

Seeing ‘China as a venture’ is simple in theory, but hard in practice. The following guidelines encapsulate this approach:

- Make sure all facts are verified on the ground. When considering any potential expansion or partnership, a lot of verification is required. Local customers, facilities, markets, companies, infrastructure, government initiatives and so on, all need to be inspected, and details rigorously verified through other sources. Verified facts are the foundation of strategy. For example, at time of writing, China is home to 121 unicorns (by comparison Europe has 36).[1] Unicorns are often seen as proof of market growth and the potential to find great partners. In reality, unicorns need to be carefully examined before any conclusion can be drawn. What is fuelling their valuation? What do they base their projections on? Are they truly suitable partners or more likely competitors? To verify these details, local teams need to meet with potential partners and review their operations, market and competitors. Only thereafter can a plan be developed.

- Work only with trusted partners. China operates at great speed, so the human risk factors are also greater. When choosing between capabilities and trust, choose trust. China is large; if a company is not successful in one location, it can try again in another. But if a company enters into a bad partnership, it can lose the entire market. Therefore, a company should not enter into a partnership or deal without understanding the counterparty’s objectives, or hire a senior manager without really knowing the person. It is essential that foreign entrants surround themselves with people they trust. Trust can come from referral, but also needs to be built up, tested and reviewed. Companies should only trust people whose benefit to their China expansion is clear and agreed upon. This particularly applies to investment.

- Keep teams compact as long as possible. Working for a foreign company is still a goal for many Chinese employees. This is not because of the higher pay (leading Chinese companies usually pay better), but due to the work-life balance and international component. While this is beneficial, companies may attract some people that look great on paper but are not that productive in practice. In addition, new entrants to the China market should not use English language skills as an assessment filter; good workers are not always good English speakers and vice versa. Until a China market strategy is formed and revenue is coming in, companies should aim to keep the team small.

- Localise products and scale fast. Given China’s unique business landscape, product localisation is essential across all business sectors. China differs in not just customer needs (both B2B and B2C), but all the way down to the nuances of domestic technology regulations and standards. The first step in localisation is to start testing the existing product in the right environment and using the feedback to improve it. The ability to localise and scale quickly is more important today than 20 years ago for foreign companies expanding to China, in order to keep up with Chinese competition and achieve a defendable market share (Figure 1). In addition, domestic competition today can often catch up with a foreign company’s product within a few years.

The key questions for China expansions are:

- how to build sustainable revenue?

- how to navigate the Chinese market?

- how to link and manage the China operations with global operations?

- how to localise, scale and compete with domestic competition?

Emerging PE managers in China use fund strategies that deploy capital, coupled with an entrepreneurial and active management role, to better faciltate portfolio companies’ expansion in the Chinese market.

Laursen van Swieten

Laursen van Swieten (LvS) is an Asia-focussed expansion investment firm. We invest in and manage China expansions of innovative European companies. We manage two funds and our focus industries are healthcare, biotech, Industry 4.0, new energy, and media and entertainment.

Active Expansion Investment refers to our entrepreneurial, very hands-on approach. We drive results. We cross the bridges that lie before us or we build them to ensure that our portfolio companies achieve successful expansions. We leverage an investment strategy that mitigates downsides while allowing Laursen van Swieten to take the lead as expansion manager.

[1] CN Insights 2021, Complete List of Unicorn Companies.

[1] McKinsey & Co. 2020, In Search of Alpha: Updating the playbook for private equity in China

[2] McKinsey & Co. 2019, The Future of Asia.

[3] International Monetary Fund Word Economic Outlook Database 2019.

Recent Comments