The evolution of China’s intellectual property protection system

With China being an innovation powerhouse, it can be difficult to remember that its modern intellectual property rights (IPR) system is a rather recent development, as the People’s Republic of China (PRC) adopted intellectual property (IP) protection policies relatively late compared to the rest of the world. Matias Zubimendi of the China IPR SME Helpdesk takes a look back at how attitudes in China towards IP changed as its economic power rose.

20th century: the origin of the legal framework

During the 1950s/60s, China’s collectivist approach to private property had a direct influence on the conceptualisation of IP. For example, regarding copyright, creations did not belong to the author but rather to a ‘collective endeavour’, making it impossible for authors to gain revenue from their works. It is not until the late 1970s that China started to establish a proper IPR system. The first step towards this was the signing of the Agreement on Trade Relations between the United States and the PRC in 1979. According to the Agreement, ‘both contracting parties agree that each party shall seek, under its laws and with due regard to international practice, to ensure to legal or natural persons of the other party protection of patents and trade marks equivalent to the patent and trade mark protection correspondingly accorded by the other party’.

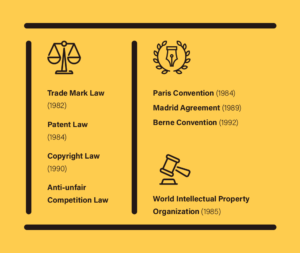

While back then the Chinese legal framework was not yet ready to comply with the provisions of the Agreement, the new legislation ushered in a move towards China’s modern IP framework with the publication of the Trade Mark Law (1982), the Patent Law (1984), the Copyright Law (1990) and the Anti-unfair Competition Law (1993). Regarding IP-related international agreements, China joined the Paris Convention (1984), the Madrid Agreement (1989), the Berne Convention (1992) and the Patent Cooperation Treaty (1993). In 1985, China also joined the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

Issues with IP enforcement

Up until the late 2000s, China was an avid absorber of foreign technology – its domestic enterprises learning from multinational companies (MNCs) that invested in the country, with the aim of building up their internal capacity to eventually directly compete with the foreign firms. This was mostly carried out at the expense of the proper enforcement of commercial laws, including IP laws. At the same time, China started to realise the importance of IP protection and proper enforcement if the country was going to transform from the ‘world’s factory of cheap products’ into an innovation powerhouse. Major IP reforms kicked off with China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. As part of its accession package, China made commitments regarding the protection and enforcement of IPRs that would bring its IP system in line with international standards.

In the early 2000s, the enforcement of IP laws and regulations in China was far from ideal, which had an impact on daily business life. For example, it was a rather common practice for Chinese companies to target senior employees of MNCs in attempts to acquire trade secrets and other valuable business-related information from them. In addition, while the central government endeavoured to improve IP enforcement, provincial and local protectionism often worked against those efforts. For instance, a 2015 study highlighted that Chinese companies litigating in their hometown were more likely to win against foreign companies. However, once these decisions were appealed in higher courts (provincial-level) the Chinese firms’ chances of winning were reduced considerably.

Rapid economic development in the 2000s brought along a significant increase in IP registrations – and complex IP disputes China’s regular courts were ill-equipped to handle. Therefore, in 2014, the Supreme Court issued the Fourth Five-year Reform Plan of the People’s Courts (2014–2018), proposing to expedite the establishment of specialised IP courts in regions with numerous IP disputes. On 31st August 2014, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC) issued the Decision on Establishment of Intellectual Property Rights Courts in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. Before the end of the year, all three courts were fully functional. Following their success, six years later, in December 2020, the NPC decided to establish an additional IP court on the southern island of Hainan.

IP courts have first-instance jurisdiction in civil and administrative cases involving patents, new varieties of plants, integrated circuit layout designs, technical trade secrets and computer software. Furthermore, decisions made by organs of the State Council or local governments regarding copyrights, trademarks and unfair competition can be appealed to the IP courts. Finally, these courts can also make decisions in civil cases on trademark recognition.

Since 2017, the Supreme People’s Court has authorised the establishment of IP Tribunals by Intermediate People’s Courts in Nanjing, Shenzhen, Wuhan, Hangzhou and 15 other cities. The specialised IP Tribunals resemble the specialised IP courts in many aspects. For example, both are intermediate-level courts and exercise jurisdictions over similar subject matters, such as patents and technology-related cases. However, while IP courts only have jurisdiction over IP cases within their own city limits, IP Tribunals have cross-regional jurisdiction over the entire province or multiple cities within that province.

Furthermore, in 2017, China established the first Internet Court in Hangzhou. Due to its initial success, in September 2018, further Internet Courts were added in Beijing and Guangzhou. These courts have jurisdiction exclusively over online copyright disputes. As a special feature, the entire litigation process happens online, making it accessible 24/7 from a phone or laptop.

On 1st January 2019, the Supreme People’s Court officially established an appellate-level Intellectual Property Tribunal. This tribunal is subject to a pilot period of three years and centralises jurisdiction over appeals involving patent infringements/invalidation and other high-technology or antitrust IP disputes.

The institutional setup also underwent important changes. On 3rd September 2018, the State Intellectual Property Office was reorganised as the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA). This move centralised the administration of patents, trademarks, geographical indications and integrated circuits layout design under one institution. Oddly, copyright administration remained under the National Copyright Administration of China.

The main purpose of this reform was to improve the efficiency of IP administration and increase its power. Before the institutional reorganisation, each type of IP was handled by a different office, creating difficulties in the management and enforcement of IPRs. Now, administrative IP enforcement is carried out by three different offices – the CNIPA, which as well as dealing with administrative actions over registered IPRs provides guidance on trademark and patent enforcement; the State Administration for Market Regulation conducts investigations, collects evidence and confiscates goods; and the Customs focusses on IP infringement at China’s borders.

The reform of the IP protection system is continuing with recent amendments to the main IP laws (Trade Mark, 2019; Copyright, 2021; Patents, 2021), intended to modernise and strengthen IP protection while giving more powers to the judicial and administrative authorities.

In the next issue of EURObiz, we will examine how these reforms to the domestic IP protection system have been received, and the indications from the Chinese Government on the future path IPR enforcement in China will take.

Matias Zubimendi is IP business advisor at the China IPR SME Helpdesk.

The China IPR SME Helpdesk supports small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) from European Union (EU) Member States to protect and enforce IPR in or relating to China, Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan, through the provision of free information and services. The Helpdesk provides jargon-free, first-line, confidential advice on intellectual property and related issues, along with training events, materials and online resources. Individual SMEs and SME intermediaries can submit their IPR queries via email (question@china-iprhelpdesk.eu) and gain access to a panel of experts, in order to receive free and confidential first-line advice within three working days.

The China IPR SME Helpdesk is an EU initiative.

To learn more about the China IPR SME

Helpdesk and any aspect of IPR in China, please visit our online portal at

http://www.ipr-hub.eu/

Recent Comments