Embrace the change, be aware of the risks

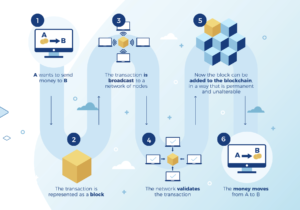

For a long time, the buzzword ‘blockchain’—simply put, a digital and decentralised ledger that records transaction information—has merely been associated with Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. While this specific combination surely was the one that gave the distributed ledger technology (DLT) renown, it is not the only, or perhaps not the most sophisticated, application of blockchain. Currently, many different DLT applications are being studied and implemented. Filippo Sticconi, national chair of the European Chamber’s Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Working Group and senior associate at GWA Greatway Advisory, looks at the options available, as well as the potential risks involved.

——————————–

Theoretically speaking, blockchain could be applied to almost every industry and business, since any database or ledger could be created and maintained using the technology. Furthermore, there are other inherent characteristics of blockchain that led it to be paired with cryptocurrencies and that are now being positively evaluated for different applications, such as: i) the ‘consensus protocol’, the process by which the nodes in the network agree on a shared data history; and ii) the cryptographic fingerprint, which is unique to each block. These features mean the information stored in the distributed ledger should be secure, private, immutable and tamper-proof, opening the technology to an immense number of possible synergies, several of which are already at an advanced stage of experimentation or implementation.

Many may have misconceived the relationship between China and blockchain in the wake of Beijing’s 2017 severe stance towards cryptocurrency and related trading activities, as they perhaps assumed the same treatment would be applied to blockchain-based technology. On the contrary, even if the principles behind blockchain (conceived as purely ‘decentralised’ and safe from third-party influence) have been revised with ‘Chinese characteristics’ to become a more controlled version, its implementation is nevertheless undeniably extensive and, in some cases, represents state-of-the-art technology.

Indications of blockchain gaining momentum in China

China files the highest amount of blockchain-related patents in the world. Most importantly, blockchain and other data-related technologies (such as quantum computers, artificial intelligence and autonomous vehicles) were included in recent state development plans as an “essential line of development”. Furthermore, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) stated that blockchain will be used alongside other emerging technologies as part of the backbone system for managing information flow in China.

Within this framework, gigantic tech firms, state-owned and private enterprises, banks and telecommunication companies, local and provincial governments, and even courts, are now jointly and severally concentrating efforts to develop, improve and implement blockchain in their respective fields.

As blockchain technology matures, what are the emerging trends?

Trial and pilot implementations are currently being carried out in China, and some applications of the technology might contribute to simplifying and/or overcoming long-standing issues, both in terms of accuracy of information and the time spent obtaining it. For instance, in the field of traceability of goods, some private Chinese tech companies currently provide services to track goods using the DLT along the supply chain from each factory to the end user. Such reliable traceability services could assist in better supervising, tracking down and solving quality issues along the supply chain. It may also be extremely helpful to curb counterfeiting and other intellectual property rights (IPR)-related infringements, which are still a massive phenomenon in China, in offline and online markets alike.

This blockchain-based system might allow for distinguishing more easily between genuine and counterfeit goods (the latter being not registered in the shared ledger or, for example, not traceable back to the rightful owner of the connected IP rights). This can save time in proving ownership of a given IP right, or in investigation and evidence collection (fundamental in anti-counterfeit and infringement procedures, and for liquidation of damages in court).

Another similar system uses the ‘time stamp’ of the transmission of a given piece of information to the ledger, which can serve as proof of creation (for instance, of a copyright) in a certain time and space. DLT is currently also being piloted in China for notarisation of evidence as a substitution for a notary public. In Hangzhou (the e-commerce capital of China), a special Internet Court is currently trialling blockchain-related evidence as proof.

When embracing progress, it is also crucial to carefully evaluate possible shortcomings, particularly considering the importance of the fields where the new technology is often being tested. The great advantages of having a distributed ledger to record information and transactions are easily perceivable in several circumstances. However, the risks connected to each aspect of the same implementations are somewhat more shady and tend not to be as evident at first, also possibly due to the pace of innovation and the highly technical background required to foresee any potential abuse.

In this regard, it is worth mentioning that, even if the distributed ledger is comparatively speaking a secure tool, it is far from invulnerable or impenetrable. According to many experts, even if not in its entirety as a chain, each ‘node’ can be isolated, attacked and possibly tampered with. Further concerns lie within the possible competitive advantages for the providers of the technology (which may be private or not) in accessing the information contained therein. Additionally, any vulnerability in the providers’ infrastructures to malicious external attacks might have critical consequences for all parties. Another issue that remains unsolved is the human factor, which, if wrongly linked with the technology, can have devastating consequences.

Even assuming that data existing in the blockchain is immutable, it is important to evaluate how to protect against incorrect or false information being inserted into the system, considering that we are in the process of assigning to the same technology the power, for example, to affect a court judgment if applied to IPR registrations, notarisation, evidence collection or smart contracts.

In a recent event hosted by the European Chamber’s IPR Working Group titled: ‘More Than Just Bitcoin: How new technologies and blockchain are changing the way for companies to do business and protect IP’, we explored advantages and disadvantages of these possible new implementations of blockchain in traceability of goods and notarisation of evidence, and how they might influence the fate of European and domestic companies in China. While these potentially remarkable changes were welcomed by all at the event, concerns were raised within many fields. From the narrow perspective of IPR protection, these mainly pertain to:

- the initial reliability of the information as inserted, compounded by the fact that it cannot be changed later on;

- the risks and responsibilities of entities providing the technology to competitors and commercial operators, as well as their eventual ability to access the content, considering that where there is encryption, there is also a key; and

- the need to explore further the actual vulnerability of the system, taking into account the degree of authority that is currently in the process of being assigned to the technology, going as far as to vest the role of evidence in a court of law and/or to replace the functions of a notary public.

These considerations are not intended to be a firm and definitive statement against blockchain; on the contrary, they should stimulate careful consideration of the technology’s shortcomings in order to better prevent them. In this new era, legislative bodies are struggling to regulate in a short amount of time great technological advancements, and to find the appropriate balance between protection of legitimate rights and innovation without slowing progress. Implementing new technologies always comes with the fear of the unknown, but the same should not stop innovation. However, before the widespread application of blockchain to such important functions and roles, we should consider the potential implications to their full extent, or else risk these issues also becoming ‘immutable’ data on the shared ledgers.

__________________

Filippo Sticconi is national chair of the European Chamber’s IPR Working Group and senior associate at Greatway Advisory (GWA). He is an Italian qualified lawyer and, as senior associate at GWA, he assists European companies in China and Chinese companies in Italy in transnational matters related to IPR, international commercial law and arbitration, and mergers and acquisitions. He has studied and worked in China since 2009, holds a Master’s in law at Alma Mater Studiorum (Bologna), and was a visiting student at the China Political Science and Law University (Beijing).

Recent Comments