Some practical tips to prepare for decoupling

European companies in China are at risk of being caught in the expanding crossfire between the US and China as they steadily decouple from one another. Jacob Gunter, senior policy and communications manager with the European Chamber, explains how the Chamber, in partnership with the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), in their recently published report, Decoupling: Severed Ties and Patchwork Globalisation, found that European Chamber members surveyed were overwhelmingly underestimating how they may be impacted by the divergence of these two major markets.

—————————

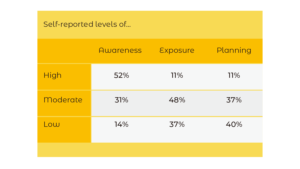

A general survey on decoupling was completed by 120 European Chamber member companies in October 2020. Respondents indicated relatively high levels of awareness surrounding decoupling, and most recognised a moderate to low amount of exposure. Only a handful reported meaningful levels of mitigation planning.

At first glance, this seems positive – European companies are generally aware, not terribly exposed and some seem to be getting their act together ahead of any further disruptions.

Unfortunately, the 60-plus subsequent interviews with some of the surveyed member companies found these self-reported levels of awareness, exposure and planning to be highly optimistic.

Awareness

The bulk of the interviews conducted initially reflected the survey findings, with companies seemingly confident in their awareness of decoupling trends. However, as most interviews proceeded, company representatives began to portray bleaker prospects. Several noted that they had not given sufficient consideration to certain issues.

These interviews showed that companies tended to view decoupling through a limited scope, chiefly looking at the United States (US)-China trade war as well as potential disruptions to supply chains as foreign companies considered leaving the Chinese market, especially American firms. Companies were right to remain confident in light of the trade war, as most have by this point found ways to cope with or outright dodge the bilateral tariffs. However, using ‘companies leaving China’ as a main indicator of decoupling is not accurate. In the European Business in China Business Confidence Survey 2020, a mere 11 per cent of European companies were considering shifting investments outside of China.

Instead, companies would do well to boost their awareness of the various layers of decoupling that are proceeding apace, nine of which are covered in extensive detail in the decoupling report:

- Macro: Political and financial

- Trade: Supply chains and critical inputs

- Innovation: Research and development (R&D) and standards

- Digital: Data governance, network equipment and telecommunications services

Exposure

Companies almost universally underestimated their exposure to decoupling. Most had a better understanding of the individual layers and how they impact their company, but very few realised how the intersections of different challenges could hamstring their operations. This was most apparent in the ‘technology ecosystem quagmire’ identified in the report; how the US and China are in the early stages of a technology divergence, especially on all things digital.

China has doubled down on its self-reliance campaign, and has clearly walled off much of its technology ecosystem to protect local champions and develop an “autonomous and controllable” digital environment. The US is declaring more and more of its ties with China to be a national security risk, with not just individual technologies being barred, but increasingly entire value chains of digital equipment and solutions now being required to be purged of anything from China. The US has also gone on the offensive with certain companies, such as Huawei, by blocking their access to American technology exports like semiconductors. European companies should examine how much of their technology will be exposed if these trends continue.

In general, the decoupling report found that China-based teams tended to have a decent understanding of their exposure to the local self-reliance campaign and its challenges. Headquarters (HQ) in Europe tended to better understand the issues arising from the US securitisation drive. However, HQs’ knowledge on the situation in China was often lacking, as was China operations’ knowledge of the US, leaving both with an incomplete picture. Bridging that divide will be a critical first move for corporates to accurately measure their exposure.

In general, there are a few areas to focus on first:

- Semiconductor disruptions: China is heavily reliant on foreign semiconductor manufacturers, manufacturing equipment and chip technology. The US has already limited access to a handful of Chinese companies. While the Biden Administration is unlikely to wield these restrictions in a wide and indiscriminate manner, these tools may still be utilised. European companies will probably not lose access themselves, but they should determine their potential exposure to both lost supplies and demand.

- Network equipment and software: The broadsides from the US aimed at Huawei and ZTE are obvious, and European companies eager to integrate equipment from those suppliers cannot overlook the potential exposure to further strikes from the US or others. However, European companies should look into the broader meaning of ‘network equipment and software’ that encapsulates the technology underpinning emerging areas like automation and the Internet of Things. Interviewed companies noted that they had a mix of American and Chinese equipment and software in their preferred systems for developing smart factories or products like autonomous vehicles.

- Digital services: China’s strict limits on foreign-invested ‘value-added telecommications services (VATS)’—for example, cloud services, data storage and management, virtual private networks and certain types of online stores—traditionally primarily affected information and communication technology/telecoms companies. However, more and more companies across all industries are developing their own VATS solutions to improve their operations and boost value and convenience for customers. Companies looking to bring these solutions to China need to be acutely aware of the restrictions involved, and begin to consider either entering a joint venture with a local company to get around barriers, or outsourcing these services to local suppliers.

Planning

European companies in China are recommended to begin strategising for potential scenarios now. First and foremost, this should include establishing a corporate taskforce that brings together teams across major markets, especially the EU, China and the US. Several companies were interviewed multiple times in order to hear from key staff in both China and at HQ. In many of these cases, staff were rarely found to be on the same page, with the perceptions of some deviating considerably from their counterparts. A taskforce can help ensure that, at the very least, everyone is working from the same information.

Ideally, this taskforce could also look into the level of company exposure mentioned above, so more coordinated responses and preparations can be made. Following the interviews, several participants went on to audit their exposure in certain areas. They found varying levels of risk and are in the midst of determining how to respond while also beginning to discuss these concerns with their suppliers and customers. This is a good start.

In the medium- to long-term, companies may need to consider how to deal with the technology divergence. Automotive makers interviewed for the report were the most likely to be looking into this, and indicated two main options in particular:

- A ‘dual system’ that would require the 100-plus essential computerised and digitalised components to be divided between two separate supply chains. Many of those components use equipment or digital solutions from the US or China, and may thus be subjected to scrutiny or restrictions in the future. This solution would create highly resilient value chains for both markets, but would be enormously costly.

- A ‘flexible architecture’ approach could be a workable alternative. Companies would try to develop products and components that are as ‘technology neutral’ as possible, which could then be adapted/localised into either market. For example, if an autonomous driving system is mostly unaffected, but the radar or global positioning system must be localised, the producer would restrict localisation to only those parts. This would be far cheaper, but risks serious disruption down the road, as all it would take is for another piece of technology to fall under the US or China umbrella requiring localisation to upend the entire supply chain.

Neither of these options are ideal, and would severely diminish companies’ economies of scale. Some companies even noted that they would be pushed out of the market as a result. Many smaller banks, for example, reported that to fully localise their systems would not only cost tens of millions of US dollars, but would also disconnect them from the very global networks that make them competitive in the few areas in which they can operate in China. If forced to localise, they would instead leave, as their already small footprints would not warrant such a sizeable investment.

There are no easy solutions, but these are examples of conversations that companies need to initiate. As well, European business should actively engage in advocating against these trends—both on their own and through chambers of commerce and industry associations, among other options—to try and steer the conversation in the right direction.

In the meantime, buckle up, and prepare for the situation to worsen.

To download Decoupling: Severed Ties and Patchwork Globalisation, click here.

The Mercator Institute for China Studies is a leading German think tank and the largest European think tank with an exclusive focus on China. The non-profit organisation was founded in 2013 by Stiftung Mercator, one of Germany’s largest private foundations. MERICS conducts research and fosters dialogue on the ascent of China as a key global player. The institute’s focus is on political, economic, social, technological and ecological developments in China and their global impacts.

Recent Comments