After Beijing’s infamous ‘airpocalypse’, Premier Li Keqiang declared war on air pollution. Official data show surprising progress in the past year. But to sustain this progress the Chinese Government must embrace more systemic and market-orientated approaches, says Calvin Quek, head of the Sustainable Finance Programme at Greenpeace in Beijing.

After Beijing’s infamous ‘airpocalypse’, Premier Li Keqiang declared war on air pollution. Official data show surprising progress in the past year. But to sustain this progress the Chinese Government must embrace more systemic and market-orientated approaches, says Calvin Quek, head of the Sustainable Finance Programme at Greenpeace in Beijing.

Beijing’s skies have long been dirty, but the ‘airpocalypse’ was something else. On 13th January, 2013, the average concentration of fine particles in the capital’s air hit a record of 755 micrograms per cubic metre (μg/m3), about double the level for a really bad Beijing smog and more than 30 times the World Health Organisation’s (WHO’s) upper limit for safe air. The choking darkness at noon made global headlines and sparked domestic outrage – including at the normally sedate National People’s Congress, whose nearly 3,000 deputies loudly booed their incoming environmental protection committee at a meeting in March that also took place under a thick blanket of smog.

The ‘airpocalypse’ spurred the government into long-delayed action. Premier Li Keqiang ordered his bureaucrats to “declare war” on pollution. D-Day came on 13th September, 2013—exactly six months after the capital’s skies darkened—when the State Council and six key ministries released a comprehensive strategy against air pollution. Enforcement followed, with the closure of coal-fired power plants and other heavy industrial polluters, especially in Beijing and surrounding Hebei.

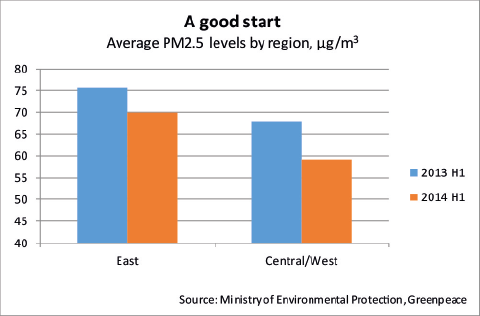

Official data suggest the ‘war’ is going well: the national average concentration of fine particles fell nine per cent in the first half of 2014 compared with a year earlier, to 65μg/m3 – a big improvement, though still far above the aspirational national standard of 35 μg/m3 (which in turn is still higher than the WHO’s 25μg/m3 ceiling). The progress is probably exaggerated: it is hard to believe that nine months of enforcement could produce such good results so quickly, and there are plenty of ways for local governments to fudge the numbers. But there is no doubt localities face intense and rising pressure to clean up their skies.

Beijing is finally serious about tackling the problem, but it still relies too much on clumsy administrative sanctions, rather than systemic measures to shift the economy on to a greener path. And there is real risk that the cleaning the air in rich cities like Beijing and Shanghai will simply lead to a transfer of pollution to poorer inland areas.

This time, we mean it

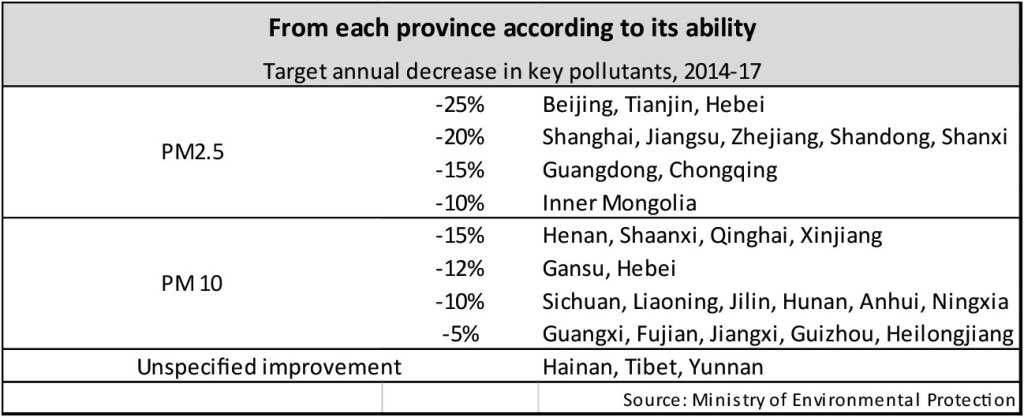

China’s air pollution strategy is a serious document. Although China suffers from various air pollution problems, the current campaign focuses on particulate matter (PM)2.5 – fine particles less than 2.5 micrometres in diameter, which are the biggest contributors to North China’s smog and by far the most serious health risk. The strategy set ambitious PM2.5 reduction targets for greater Beijing, greater Shanghai and Guangdong’s Pearl River Delta region; more modest targets followed for most other provinces.

problems, the current campaign focuses on particulate matter (PM)2.5 – fine particles less than 2.5 micrometres in diameter, which are the biggest contributors to North China’s smog and by far the most serious health risk. The strategy set ambitious PM2.5 reduction targets for greater Beijing, greater Shanghai and Guangdong’s Pearl River Delta region; more modest targets followed for most other provinces.

The plan makes some effort to move beyond the top-down enforcement approach that traditionally characterises Chinese government campaigns. Of its six focus areas, three directly address the key sources of PM2.5 in the usual way, but two relate to improving the incentives of local officials and—perhaps more surprisingly—create a bigger role for civil society organisations. The sixth requires major cities to set up emergency response plans to deal with one-off events like Beijing’s ‘airpocalypse’.

The first three goals are to eliminate old and excess capacity in polluting heavy industries (notably steel, cement, glass and bricks) and the installation of environmental-protection equipment in the capacity that remains; accelerating the shift away from coal-fired power plants to cleaner gas-fired ones; and imposing higher emission and fuel-efficiency standards on motor vehicles. All these objectives have been around for a decade or more; the new pollution strategy simply sets more aggressive targets and invites one to accept that Beijing is now really serious about enforcing standards that it had difficulty making stick in the past.

The first three goals are to eliminate old and excess capacity in polluting heavy industries (notably steel, cement, glass and bricks) and the installation of environmental-protection equipment in the capacity that remains; accelerating the shift away from coal-fired power plants to cleaner gas-fired ones; and imposing higher emission and fuel-efficiency standards on motor vehicles. All these objectives have been around for a decade or more; the new pollution strategy simply sets more aggressive targets and invites one to accept that Beijing is now really serious about enforcing standards that it had difficulty making stick in the past.

Of the two incentive-based goals, one is a hoary old chestnut: making environmental targets a bigger part of local officials’ performance reviews. This has been talked about, and allegedly implemented in some places, over the past decade with little visible impact. Officials still tend to assume they will be judged on economic growth and maintaining social stability, and that tricky, growth-retarding policies like environmental protection are not in their interests. The new rules, which the government published in May 2014, provide very specific benchmarks for assessing officials’ performance in reducing air pollution.

The more interesting goal is increased transparency. In essence, the government is pushing for more air-quality data to be collected and released, and seems comfortable with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) using this data to put pressure on polluting companies and local governments.

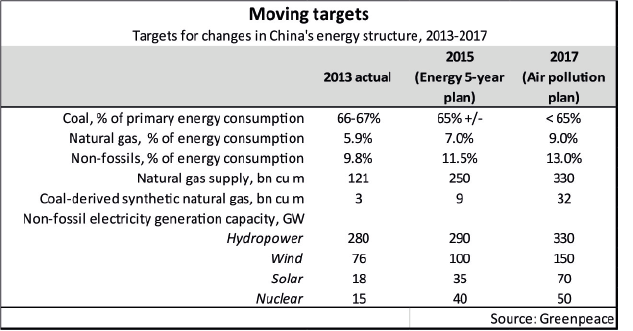

Another important element of the pollution plan is an effort to integrate it with the national energy plan, which makes sense given that coal burning contributes 45–50 per cent of national PM2.5 emissions, and transport fuel emissions account for another 15–20 per cent. In theory, huge progress toward reducing PM2.5 emissions could be achieved by shifting the national energy mix away from coal and towards cleaner fuels (such as natural gas, nuclear and renewables), and by improving the efficiency of the transport fleet.

Another important element of the pollution plan is an effort to integrate it with the national energy plan, which makes sense given that coal burning contributes 45–50 per cent of national PM2.5 emissions, and transport fuel emissions account for another 15–20 per cent. In theory, huge progress toward reducing PM2.5 emissions could be achieved by shifting the national energy mix away from coal and towards cleaner fuels (such as natural gas, nuclear and renewables), and by improving the efficiency of the transport fleet.

The problem with targets: hitting them

This is all well and good, but Beijing has promulgated plenty of energy and environmental plans and targets in the past, and its record in hitting them is less than stellar. The country fell short of meeting its much-heralded, energy-intensity reduction target of 20 per cent in the 11th Five-Year Plan (2006-2010), which was the focus of intensive enforcement efforts; and it only got as close as it did (-19 per cent) by temporarily shutting down large swathes of energy-hogging factories in the plan period’s closing months.

The industrial-closure approach creates the temptation to shift pollution from more to less visible locations. This is evident from a comparison of Hebei and Jiangsu. Hebei, which surrounds Beijing, endured a draconian clean-up of its steel, power and coke industries[1] and saw its reported PM2.5 level fall by seven per cent year-on-year in the first half of 2014; Beijing’s level fell 10 per cent (these figures are reasonably consistent with power-consumption data and with the visible reduction in the number of dire smog days in Beijing). But Jiangsu, in east-central China, was one of eight provinces reporting an increase in PM2.5 levels. This appears to have been a direct result of a heavy industrial boom: the province’s industrial production rose 10 per cent in the first half of 2014, and steel production grew eight per cent. Press reports suggest that as steel plants closed in Hebei, new production fired up in northern Jiangsu. In other words, the steel industry’s PM2.5 emissions are being moved around, but not eliminated.

The problem with systems: building them

The problem with systems: building them

Examples like this suggest that a more systemic approach would be more preferential to the ‘strike hard’ enforcement tactics that Xi and his colleagues favour.

Historically, China has relied heavily on administrative measures, while doing a poor job with regulatory, market and institutional levers. The current war on pollution is so far not much different: most action has come through administrative enforcement. More needs to be done to embed pollution control in China’s economic and political systems.

Little progress has been made on market mechanisms: a higher tax on coal, and a new comprehensive carbon tax have been discussed for years but there is no sign of imminent implementation of either. Experimental cap-and-trade programmes, with markets for carbon emission permits, are piloting in seven cities, but the chances of expanding beyond the pilot stage any time soon are dim. The Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) remains bureaucratically weak and under-resourced, and the concrete impact of a revised Environmental Protection Law (to take effect in January 2015) is unclear.

Little progress has been made on market mechanisms: a higher tax on coal, and a new comprehensive carbon tax have been discussed for years but there is no sign of imminent implementation of either. Experimental cap-and-trade programmes, with markets for carbon emission permits, are piloting in seven cities, but the chances of expanding beyond the pilot stage any time soon are dim. The Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) remains bureaucratically weak and under-resourced, and the concrete impact of a revised Environmental Protection Law (to take effect in January 2015) is unclear.

There are two bright spots. One is the move towards greater collection and disclosure of air pollution data, and the willingness (so far) to let NGOs use this data to gin up public pressure against polluters. A second is the recognition that air pollution is a regional issue that cannot be solved within the limits of individual administrative jurisdictions.

Yet even here caution is advisable. There is still wide variance in both the availability and reliability of air pollution data, and it remains to be seen how long Xi’s government (which in general has tried to tightly control both the media and civil society) will tolerate unregulated citizen pressure on polluters.

Adding it all up, the likely verdict is that like many items on Xi Jinping’s reform agenda—anti-corruption, SOE restructuring, residence permit reform—the war on pollution will end neither in outright victory nor defeat. The key difference between this ‘war’ and previous environmental efforts is that this time the government acknowledges that air pollution is not simply a by-product or necessary evil of economic growth, but rather is an exemplar of unhealthy trends that directly threaten China’s ability to keep its economy growing over the next couple of decades.

Calvin Quek heads the Sustainable Finance Programme at Greenpeace in Beijing. This article is adapted from his piece Bringing Back the Blue Sky Days, which was first originally published by Gavekal Dragonomics in their publication China Economic Quarterly.

[1] Cleaning Up Coketown: Can air pollution be controlled?, China Economic Quarterly, March 2014, http://research.gavekal.com/content.php/9819-China-CEQ-Q1-2014-Cleaning-Up-Coketown-Can-Air-Pollution-Be-Controlled

Great article! Unfortunately there is NO mention of GeoEngineering/weather modification upper atmospheric aerosols in which are the major cause of the fine particulate haze. Those elements are aluminum oxide, barium salt, strontium and others. Perhaps that source needs to be cut off.