While manufacturing has traditionally been a pillar of China’s economic growth engine, overreliance on low-tech manufacturing carried the risk of leaving China stuck in the ‘middle-income trap’.[1] Made in China 2025 (MIC2025), an industrial policy plan launched in 2015, was a key part of China’s overall strategy to prevent this by developing new growth drivers through the expansion of advanced manufacturing capabilities. The plan stood out from previous Chinese industrial policies for its ambitious market share targets,[2] including an overarching goal of achieving 70 per cent domestic market share for “core basic components and key basic materials” by 2025. It also prescribed specific technological targets, calling on domestic firms in its 10 key sectors to launch domestic versions of core technologies by 2025.

A decade on, MIC2025’s core principles have been tweaked, expanded upon and repurposed to fit a wider scope of strategic industries, indicating that China will continue with renewed ambition many of the practices that MIC2025 either introduced or reinforced. In addition, during this time period, the overall aim of MIC2025 has been gradually aligned with China’s new policy priorities – namely ‘dual circulation’ and the drive to achieve self-reliance, even to the point of realising “self-sufficiency in scientific and technological infrastructure.”[3] In short, the plan is not just about creating more globally competitive domestic companies, it is about creating the conditions that will allow China to lead in the technologies that will define the future global economy.

Different shades of success

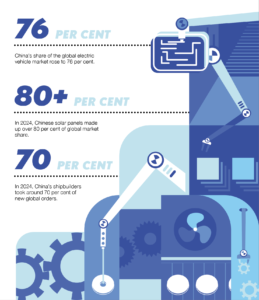

While some of MIC2025’s specific sectoral targets have not been achieved, its general goal of further modernising China’s overall manufacturing sector has been advanced significantly. For example, in 2024, China surpassed Germany in the number of industrial robots per 10,000 workers, meaning that, at least by this metric, China’s level of industrial automation is now greater than that of any European country.[4] Since 2015, more Chinese companies in MIC2025 sectors have become world leaders, allowing China to capture significant global market share: in 2024, China’s shipbuilders took around 70 per cent of new global orders;[5] China’s share of the global electric vehicle (EV) market rose to 76 per cent;[6] and Chinese solar panels made up over 80 per cent of global market share.[7]

Despite, impressive progress on paper, MIC2025’s implementation has resulted in a number of challenges and negative externalities. For example, the mixture of subsidies and policy support has led to countless—often significant—inefficiencies, with some industrial segments becoming saturated as a result. This, in turn, has resulted in ‘involution’, a term which, in an industrial context, refers to unhealthy competition, leading to companies investing ever increasing resources without generating commensurate returns. Several of the MIC2025 industries that performed best on sectoral targets—namely NEVs and wind turbines—have also experienced damaging price wars.[8]&[9]

There are also areas in which MIC2025 underperformed by its own targets, evidence that industrial policy alone is not enough to ensure success. For example, China’s self-developed commercial passenger jet, the C919, is still predominantly reliant on foreign suppliers for its key components, leaving it far from the degree of self-reliance that China is aiming for.[10]

China’s pursuit of near self-sufficiency in advanced semiconductors—something no single country has achieved—is also evidence of MIC2025’s limitations. China has made advances in key semiconductor technologies, but its inability to produce extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines has so far prevented it from being able to produce the most cutting-edge chips at a scale that would allow commercialisation. While it is possible that a sudden advance or shift in technology could see China surge ahead, there is no way to guarantee that it would stay there. Therefore, despite being difficult in the face of US restrictions, the only plausible way for China to ensure a reliable supply of the most advanced chips is to regain access to the global semiconductor ecosystem, something that its pursuit of self-sufficiency is at odds with.

FIEs a useful bridge

For foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs), individual outcomes of each MIC2025 sector vary largely based on the level of technology that their Chinese competitors possess. For sectors in which China has achieved a high level of self-reliance, FIEs are more likely either to face challenges selling their product or find themselves uncompetitive.

Taking high speed trains as an example, China has achieved a high degree of self-reliance, with only a couple of components—bearings and screws—still sourced from overseas. [11]&[12] Because of this, European Chamber members in the rail sector have suffered a significant loss of market share in recent years. Another example, in the middle of the ‘self-reliance spectrum’, is biopharmaceuticals, a sector in which Chinese firms have some advanced products but are not yet able to produce every type of drug at the same quality or price. European Chamber members in the biopharmaceutical sector have found success concentrating on high-end products, relying on their long-standing reputation for quality and safety, as well as innovation, to lead in this segment. A final example, at the far end of the spectrum, is aviation, a sector in which China is still reliant on foreign suppliers – likely not out of choice, but because these suppliers act as a bridge, enabling China to produce a product—the C919—that would otherwise be several years away.

Exporting MIC2025’s side effects

China’s trade with the EU in products from MIC2025 sectors is a good proxy for measuring the technological capabilities of Chinese companies. For sectors in which China has had the most success, exports to the EU have risen. Key examples of this include NEVs, rail technology, electrical power equipment and some next generation IT products such as telecommunications network infrastructure. Interestingly, all of these sectors have seen the EU take defensive action to protect the Single Market from perceived or potential market distortions.[13],[14],[15]&[16]

Some of the spikes in exports from China to the EU seen in some MIC2025 sectors reflect increasing international concern over China’s industrial policies. When subsidies and other forms of policy support create an overcrowded environment in their home market, Chinese companies turn to exports as a source of relief.

While this practice can be viewed positively, in that it makes key technologies—including those important for the green transition—more affordable, it also exports many of the market distortions that the MIC2025 plan has created in the China market.

Many FIEs have suffered significant damage

For FIEs in many of MIC2025’s sectors, it is too late to reverse the negative effects of China’s industrial policies. For example, in the automotive sector, the emergence of NEV technology made market access barriers intended to constrain FIEs in the internal combustion engine (ICE) segment unnecessary. Even the requirement to enter into a joint venture (JV) with a Chinese company to produce vehicles in China—which was perhaps the most significant market access barrier—has been removed.[17],[18]&[19] This indicates that many of the barriers that have been traditionally faced by FIEs are there to provide a temporary boost to domestic industry, and can be dismantled once market conditions favour domestic competitors.

The impact of these types of market access barriers is long lasting, and simply removing them does not eliminate competitive disadvantages that have arisen as a result of years of unequal treatment, rather it starts a vicious cycle that is difficult to exit. For instance, a loss of business due to market access restrictions can result in less willingness from European companies’ headquarters to invest further in China, which can have the consequence of rendering the China subsidiary less competitive even if its market conditions eventually improve overall.

The opposite can be true for Chinese companies, where, in some cases, market access barriers have helped ease them into a virtuous cycle. The ability to rapidly gain domestic market share, often contrary to market forces, can quickly improve their profitability allowing them to scale up and expand globally.

MIC2025 core principles live on through ‘new productive forces’

Despite the negative externalities and inefficiencies created by MIC2025, China looks set to continue and expand the same industrial policy playbook. ‘New productive forces’, introduced in 2023, encapsulates the main MIC2025 ideas of developing and then leading in strategic and emerging industries, but extends the scope beyond the 10 sectors that MIC2025 identified.[20] The pursuit of self-reliance, and even self-sufficiency, in critical industries will therefore continue, but through a framework that is not only broader but also lacking in specificity. While some FIEs will have an important role to play in some sectors at certain times, the ultimate goal appears to be to make them easily controllable and substitutable.[21]

This approach, however, overlooks the fact that developing critical technologies is a dynamic, continuous pursuit that requires a predictable outlook. Even if China can achieve all of its MIC2025 targets, doing so in a way that puts the country at odds with other major economies could be costly in the long run, potentially cutting it off further from access to future technologies as other countries seek to protect their own industrial capabilities and positions in home and third-country markets. It does not account for the fact that all major economies are now far more cognisant of China’s industrial policy practices and the negative impact that they can have on their own respective markets, and are prepared to tackle any resulting market distortions accordingly.

At a time when the United States is bringing unprecedented uncertainty to the future of global economic interdependences, it would be in China’s interests to demonstrate to the EU that it is willing to compete fairly in a way that allows for a long-term, mutually beneficial EU-China economic relationship. This could be achieved, at least in part, by shifting away from the highly coordinated industrial policy framework that MIC2025 introduced—and which seems will live on under ‘new productive forces’—and returning to bold market-orientated reforms that will allow Chinese and foreign companies to compete on a level playing field. This would also have the added benefit of reducing the prevalence of ‘involution’ and overcapacity, which have characterised many of the MIC2025 industries and the Chinese economy in general in recent years.

Austin Bliss is a policy and communications coordinator at the European Chamber and was the lead writer of Made in China 2025: The Cost of Technological Leadership. The full report can be downloaded here: https://www.europeanchamber.com.cn/en/publications-archive/1274/Made_in_China_2025_The_Cost_of_Technological_Leadership

[1] The ‘middle-income trap’ refers to countries that fail to become high-income despite experiencing economic growth and decreased poverty rates. Feingold, S, The ‘middle-income trap’ is holding back over 100 countries. Here’s how to overcome it, World Economic Forum, 4th September 2024, viewed 10th March 2025, <https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/09/middle-income-trap-world-bank-economic-development/>

[2] From 1978 onwards, China used direct intervention in priority, long-term industries to achieve its development goals. By the 1990s, China began to identify and develop high-tech and ‘pillar’ industries. The country dialled back on industrial policy following its entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, but embraced it again in earnest during the global financial crisis in 2008. Into the mid-2010s, China further ramped up its industrial policy with more ambitious targets, like MIC2025. Wei, J, China’s Industrial Policy: Evolution and Experience,United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, July 2020, viewed 7th November 2024, <https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/BRI-Project_RP11_en.pdf>

[3] The official English translation of the decision of the Third Plenary Session of the 20th Communist Party of China Central Committee uses the term ‘infrastructure’, however the Chinese version of the same text uses the term ‘jichu tiaojian’ or ‘basic conditions’, a broader term which is inclusive of physical infrastructure. Full text: Resolution of CPC Central Committee on further deepening reform comprehensively to advance Chinese modernization, Xinhua,21st July 2024, viewed 21st February 2025, <https://english.news.cn/20240721/342df6c6e05c4e1a9ce4f6e3b933007b/c.html>; Resolution of CPC Central Committee on further deepening reform comprehensively to advance Chinese modernisation, Xinhua, 21st July 2024, viewed 21st February 2025, <https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/202407/content_6963770.htm>

[4] Global Robot Density in Factories Doubled in Seven Years, International Federation of Robotics, 20th November 2024, viewed 22nd January 2025, <https://ifr.org/ifr-press-releases/news/global-robot-density-in-factories-doubled-in-seven-years>

[5] China secures 70% of global green ship orders in first three quarters of 2024: report, Global Times, 10th October 2024, viewed 6th February 2025, <https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202410/1320959.shtml>

[6] Hawkins, A, China’s share of global electric car market rises to 76%, The Guardian, 3rd December 2024, viewed 6th January 2025, <https://www.theguardian.com/business/2024/dec/03/chinas-share-of-global-electric-car-market-rises-to-76>

[7] Solar PV Global Supply Chains – Executive Summary, International Energy Agency, viewed 22nd January 2025, <https://www.iea.org/reports/solar-pv-global-supply-chains/executive-summary>

[8] Ren, D, A bleak 2025 awaits China’s 30,000 car dealers as price war piles on US$24 billion losses, South China Morning Post, 5th January 2025, viewed 6th February 2025, <https://www.scmp.com/business/china-business/article/3293353/chinas-30000-car-dealers-face-bleak-2025-price-war-piles-us24-billion-losses?module=inline&pgtype=article>

[9] Xue, Y, China’s wind-turbine makers vow ‘self-discipline’ in pledge to end price war, South China Morning Post, 17th October 2024, viewed 6th October 2025, <https://www.scmp.com/business/climate-and-energy/article/3282739/chinas-wind-turbine-makers-vow-self-discipline-pledge-end-price-war>

[10] Kennedy, S, China’s COMAC: An Aerospace Minor Leaguer, Chinese Business & Economics, 7th December 2020, viewed 22nd January 2025, <https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/201204_Kennedy_COMAC.pdf>

[11] Are Chinese bearings really that lousy? As Chinese high-speed trains are being exported, this one part must still be imported, Wang, Tengxun, 29th December 2023, viewed 5th February 2025, <https://news.qq.com/rain/a/20231229A05QFL00>

[12] China’s high-speed trains have a critical dependency on Japanese screws, China really can’t make screws that never loosen?, Sohu, 27th April 2023, viewed 5th February 2025, <https://m.sohu.com/a/671540313_121687414/?pvid=000115_3w_a>

[13] Commission opens first in-depth investigation under the Foreign Subsidies Regulation, European Commission, 16th February 2024, viewed 22nd January 2025, <https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_887>

[14] EU imposes duties on unfairly subsidised electric vehicles from China while discussions on price undertakings continue, European Commission, 29th October 2024, viewed 22nd January 2025, <https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_5589>

[15] EU starts investigation into Chinese wind turbines under new Foreign Subsidies Regulation, Wind Europe, 9th April 2024, viewed 24th February 2025, <https://windeurope.org/newsroom/press-releases/eu-starts-investigation-into-chinese-wind-turbines-under-new-foreign-subsidies-regulation/>

[16] Commission moves to protect EU mobile access equipment industry from dumped imports,Directorate-General for Trade and Economic Security, 9th January 2025, viewed 24th February 2025, <https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/news/commission-moves-protect-eu-mobile-access-equipment-industry-dumped-imports-2025-01-09_en>

[17] Special Administrative Measures for Foreign Investment Access (Negative List) (2021 Edition),National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), 27th December 2021, viewed 6th February 2025, <https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/fzggwl/202112/t20211227_1310020.html?code=&state=123>

[18] Special Administrative Measures for Foreign Investment Access in Pilot Free Trade Zones (Negative List) (2021 Edition), NDRC and MOFCOM, 27th December 2021, viewed 6th February 2025, <https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/fzggwl/202112/t20211227_1310019.html?code=&state=123>

[19] In practice, foreign-invested vehicle manufacturers still face regulatory barriers that prevent them from optimising their investments in China, including through the restructuring of existing operations, adjusting the foreign equity ratio of existing JVs and building new vehicle production plants. For more information, see the European Business in China Position Paper 2024/2025, European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, 11th September 2024, viewed 6th February 2025, pp. 188–189, <https://www.europeanchamber.com.cn/en/publications-archive/1269/European_Business_in_China_Position_Paper_2024_2025>

[20] Introduced by President Xi Jinping in September 2023, the “term refers to new productive forces that emerge from continuous breakthroughs in science and technology, driving strategic future and emerging industries that may introduce disruptive technological advancements in an era of intelligent information.” Explainer: What do “new productive forces” mean?, Xinhua, 21st February 2024, viewed 6th February 2025, <https://english.news.cn/20240221/3e0d1b79a39f4e6c89724049558e1082/c.html>

[21] For more information on how FIEs are being moulded into more controllable and thus substitutable entities, please see Siloing and Diversification: One World, Two Systems, European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, 9th January 2025, viewed 22nd January 2025, p. 6, <https://www.europeanchamber.com.cn/en/press-releases/3682>

Recent Comments