How China and the WTO agreed to disagree over trade rules

Always ready with delightful policy jingles, Beijing has repeatedly described China’s two decades of World Trade Organization (WTO) membership as “embracing the world with open arms”.[1] This giant group hug got off to a shaky start and led to some chafing, but it has also stood the test of time. Neither side denies the divergence between Chinese and global economic visions for the near future, but all involved hope for improvement. This article by Gabor Holch of Campanile Management Consulting calls for due credit to Beijing’s participation in the WTO over two decades that dramatically changed China, the world, trade and relevant organisations.

Why China wanted in

At the turn of the millennium, China needed urgent investment to support a rapidly growing economy. Two decades of reform and opening up had proven marketisation to be an effective antidote to a nosediving state-planned economy, but reform cost money, and Beijing had to keep the momentum going. China’s struggling firms and vigorous workforce had reconnected with global markets, but the ties were weak. Its ‘most favoured nation’ status with the United States (US) required annual Congressional approval; rejection could have resulted in sky-high tariffs and snowballing reactions from Japan, the European Union (EU) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Therefore, Beijing’s jubilant reaction to WTO accession illustrated that it expected participation to “expedite the process of China’s reform and opening, the cleaning up of laws and regulations, an impartial, efficient judicial system, and competition to the country’s inefficient state-owned enterprises (SOEs).”[2] In other words, the WTO would not only bring much-needed foreign investment but also prepare China for receiving it.

Why the WTO wanted China

Beyond the hope that the above would materialise, China’s accession promised to solve complex political problems. The WTO’s predecessor, the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), had lasted half a century before its 1994 Marrakesh Summit founded the WTO. Over half of the world’s nations had joined the GATT, but China kept slipping away as its post-war national identity was formed. The Nationalist (国民党Guomindang) Government was an early GATT signatory but lost authority over most of China’s one billion consumers. The 1971 transfer of Taipei’s United Nations seat to Beijing had stranded the GATT between a member hostile to markets and a cooperative non-member. Since statehood is not a precondition of WTO membership, including both promised to ease cross-strait conflict, at least on the level of foreign trade. Beijing’s own vision for accession and Washington’s vocal hope that the WTO would ‘help China play by the rules’ boosted such hopes well into the first decade of the new partnership.

What China joined

The conditions and balance sheet of China’s membership evoke endless debates as well as pervasive urban legends. We may never know for sure if the 1999 bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade triggered some guilt-induced leniency in Western leaders towards China, or whether the following year Premier Zhu Rongji personally intervened to stop a visiting US delegation from defiantly boarding their flight, thus saving last-minute accession talks.

Regardless, credible experts agree that, as former WTO Director-General Pascal Lamy said, “China did not join the WTO on the cheap”.[3] In fact, conditions for China were set higher than for any previous developing nations. In its Accession Protocol, Beijing committed to “letting markets rather than the state set prices, equalise trading rights for state and private firms, improving the transparency of economic policy, non-intervention in the operation of the market, non-discrimination between domestic and foreign firms, and strengthening the rule of law in governing the economy,” summarises Yeling Tan, author of Disaggregating China Inc.[4] Furthermore, unlike most members, China was required to elevate WTO rules to the status of national legislation.

What happened in the past 20 years?

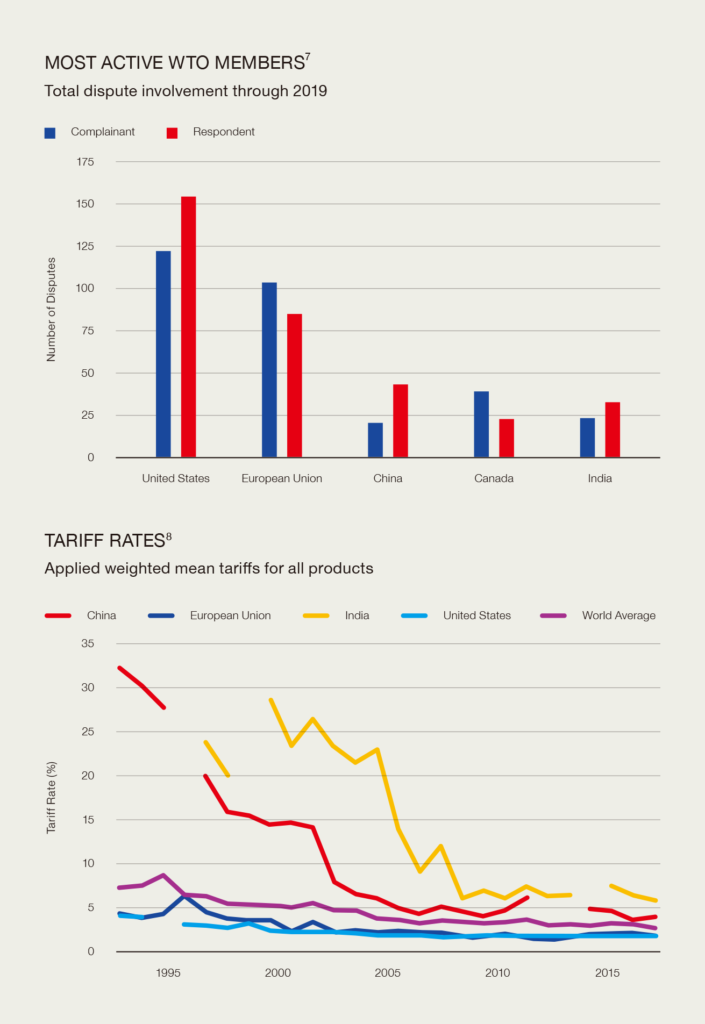

All assumed that China would catch up fast with the preconceived vision, China’s chief negotiator Long Yongtu told the WTO in 2011.[5] Indeed, the rise of the Chinese economy was spectacular. In the first decade of membership, China’s import-export volume grew from US dollars (USD) 0.5 billion to USD 3.0 trillion, and its per capita gross domestic product (GDP) rose from the level of Sudan to that of Mexico. China also learned the rules fast, becoming the third most active member after the US and the EU.[6]

But, along the way, Beijing decided to rewrite rather than follow the curriculum. Digressing from the agreed plan during the 2007-8 financial crisis resulted not only in selective compliance with WTO decisions but also a rhetoric of China providing an alternative economic model. The global authority of the US was undermined as Washington wrestled with the economic crisis on both the domestic and international fronts, and China promptly filled the rhetorical vacuum. A decade later, as then-US President Donald Trump openly pondered withdrawing from the organisation, Chinese President Xi Jinping delivered a scornful speech on the sorry state of global free trade at the 2017 Davos World Economic Forum.

What is happening now?

Ideologically loaded debates abound on whether China is the WTO’s disruptive genius or a student with an attention-deficit disorder. Mainstream Western economists agree that China’s economic reform stalled towards the end of the Hu Jintao administration; its tariffs and other, non-trade barriers still far exceed world standards. The reasons for the contradiction between what we hear and see from China are diverse, best illustrated by the two most frequent complaints: the dominance of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the Chinese economy, especially as competitors to foreign firms; and forced technology transfers to Chinese firms. As mentioned previously, China committed to non-intervention and non-discrimination from state to market, but its accession documents did not specifically mention the role of SOEs. In Beijing’s eyes, owning an energy firm or an airline is not intervention. As for technology transfers, China insists that foreign firms engage in such practices of their own volition: WTO rules regulate members, not companies.

Experts grudgingly agree. “China didn’t cheat: WTO rules have been weak,” reckons Pascal Lamy. In a way, the main source of trouble is China’s success. Accession criteria were best suited to liberalising medium-sized candidates like Croatia and Hungary, and the WTO underestimated the agility of China’s titanic state-controlled economy. For instance, legislation specific to China’s Special Economic Zones (SEZs) that host most foreign firms is not accountable to WTO rules. Essentially, as former European Chamber President Mats Harborn pointed out to CGTN in 2018, SEZs and the rest of China are two parallel economies.[9] This separation enables China to exclude foreign firms from public procurement and entire sectors through its infamous ‘negative list’ and other measures, while it still enjoys WTO membership access to other market economies without similar protective mazes. Chief negotiator Long eloquently summarised China’s attitude to transparency in 2011: “We didn’t believe in it. An old Chinese proverb says, there is no fish in clear waters.”[10]

What are the prospects?

Both sides appreciate the complex and dynamic nature of China-WTO relations. Trump and his followers were outliers: those with authority over the matter are committed to engagement and joint reform, though mindful of what Lamy called “ten years of convergence followed by ten years of divergence”. WTO members increasingly demand further liberalisation in return for continued openness towards Chinese firms. As former President Harborn told CGTN: “SEZs were an experiment in opening up—now it’s time to open up.” But opposing forces between reform and consolidation may limit China’s options. Powerful interests in existing SEZs hinder the creation of competing entities and, rather than empowering private firms, President Xi Jinping has entrenched SOEs. Specific issues like technology transfer demands and cross-strait relations show insufficient progress. While the WTO patches regulatory gaps, China’s state and favoured non-state actors leverage government resources for prominence abroad and dominance at home, while national and WTO principles undermine US and EU threats to adopt China’s protectionist tactics in retaliation. Market volatilities might upset this fragile balance; if they don’t, China has indeed created an alternative global trade regime – although not the one it intended.

Gabor Holch is an intercultural leadership consultant, coach and speaker working with executives at Asian and European branches of major multinationals. His Shanghai-based team, Campanile Management Consulting, has served 100+ clients in 30+ countries since 2005. An expat since age four, China-based for 19 years and working globally, Gabor is a Certified Management Consultant (CMC) in English and Mandarin, certified consultant at the management academies of half a dozen global corporations and licensed in major assessment tools including DISC, the Predictive Index and MBTI.

[1] Full text: China and the World Trade Organization, State Council, 18th June 2018, viewed 2nd November 2021, <http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2018/06/28/content_281476201898696.htm>

[2] How the WTO Changed China’s Economy, Foreign Affairs, 16th February 2021, viewed 2nd November 2021, <https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-02-16/how-wto-changed-china>

[3] China and the WTO: (How) can they live together?, Bruegel, 28th April 2021, viewed 2nd November 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cy3v_aUaKPc&t=2968s>

[4] ‘Disaggregating China Inc., with Yeling Tan’, Harvard Fairbanks Center for Chinese Studies podcast, 16th October 2021, viewed 2nd November, <https://podcasts.apple.com/hk/podcast/harvard-fairbank-center-for-chinese-studies/id1255938359?l=en&i=1000538712289>

[5] Interview with the Chief Negotiator of China’s WTO accession, WTO YouTube Channel, 2012, viewed 2nd November 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eFn1ytKmNfc&list=WL&index=26>

[6] How Influential is China in the World Trade Organization?, Center for Strategic and International Studies,viewed 3rd November, <https://chinapower.csis.org/china-world-trade-organization-wto/>

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] China’s adaption to the world economy through WTO, CGTN, 2018, viewed 3rd November 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TVOsnKnA6JM&list=WL&index=28>

[10] Interview with the Chief Negotiator of China’s WTO accession, WTO YouTube Channel, 2012, viewed 2nd November 2021, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eFn1ytKmNfc&list=WL&index=26>

Recent Comments