How to create the best possible terminal?

The container handling industry is constantly changing. In addition to developing new or improved products, the main focus for the future is on new kinds of services, such as guaranteed availability and performance. The ultimate goal of a container terminal is to serve the shipping lines and inland logistics companies as smoothly as possible. At the end of the day, their business performance is measured by container moves. Jari Hämäläinen and Eveliina Vuolli of Kalmar discuss the best approach to working on complex projects…such as constructing a competitive container terminal.

Building container terminals is still project-oriented

Building a new or refurbished container terminal is a massive project that involves various suppliers, which means the business and operations of a container handling equipment supplier is highly project oriented. To execute such a project, it is possible to agree on a fixed content, fixed price and final delivery date, and then just do it. However, when building a modern terminal with state-of-the-art automation systems and digital services, the ultimate goal becomes more abstract and a little less clear. It becomes a question of how to plan the final outcome accurately two years before completion.

A new approach for complex projects

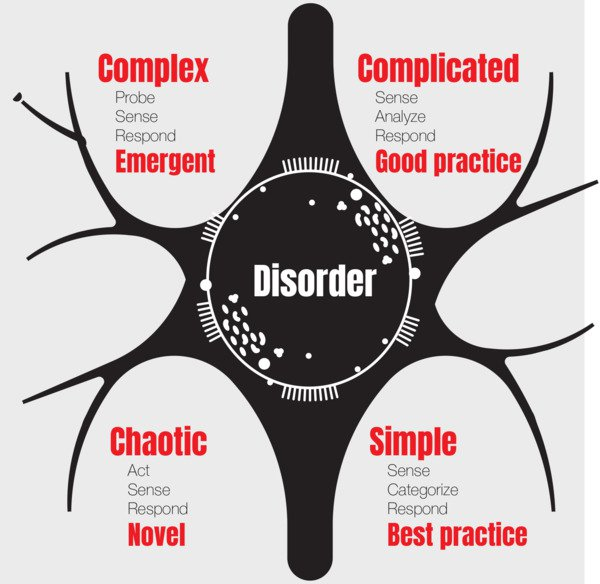

What if all the stakeholders rethought the way they work together instead of planning two years ahead? The Cynefin framework, created by Dave Snowden, could help reformulate the thinking process. This conceptual model proposes a different approach to aid decision-making and solve different kinds of problems. The idea of the Cynefin framework is that it offers decision-makers a ‘sense of place’ from which to view their perceptions.

The Cynefin (pronounced kuh-NEV-in; a Welsh word for ‘habitat’ or ‘familiar’) framework introduces five domains: simple, complicated, complex, chaotic, and a centre of disorder. The different domains help us recognise the situation we are in and select the most suitable decision-making and management style for this context. The simple domain represents the ‘known knowns’. This means that there are rules in place and the relationship between cause and effect is clear. The complicated domain consists of the ‘known unknowns’. There is a relationship between cause and effect, but identifying them requires analysis or expertise. The complex domain represents the ‘unknown unknowns’. Cause and effect can only be deduced in retrospect, and there are no right answers. In the chaotic domain, there is no relationship between cause and effect, so your primary goal is to establish order and stability. If you don’t know where you are, you’re in the disorder domain. The primary goal there is to move to a known domain by gathering information.

When conducting a project similar to others done several times before, the context according to the Cynefin framework is the ‘complicated domain’. There are several variables in the process, but experienced product and project personnel are able to analyse and handle the issues. However, when creating a novel solution (e.g. a modern terminal with brand new automation systems and digital services), it becomes a ‘complex domain’. In this situation, we need to rely on emergent solutions and experimentation. Cynefin calls this process “probe–sense–respond”.

Successful execution requires the partners to focus on agreeing on a final goal where the ultimate solutions will be defined and implemented jointly during the project.

Collaboration at the next level

Let’s take an example. Ambitious investors decide to build an advanced greenfield container terminal that will attract inland and maritime customers by bringing them high predictability and fully transparent information flow from inland logistics through the container terminal to shipping lines. They decide to start operations with a proven automated container-handling system and extend the operation in the second phase by spearheading the latest and unproven industry 4.0 technologies in order to achieve full transparency in the container logistics chain. To achieve their goals, they need to collaborate with several partners, including the port authority, civil engineering companies, container handling equipment suppliers, enterprise resource planning and terminal operating system suppliers, and finally Internet of Things (IoT) and information technology (IT) companies to create a fully transparent solution that does not yet exist in the industry.

In phase one of the project, they decide to choose their suppliers using a traditional tendering process where the goal is fixed. They decide to do it by defining a functional description of the task at hand and leave the details of the technical solution to the suppliers. In this case, the operator is moving in the ‘simple’ domain, where they assume that they know the final goal and trust the supplier’s ability to handle the final details and make delivery.

Phase two of this project is clearly moving to the ‘complicated’ or even ‘complex’ domain where nobody can yet define the exact outcome. To succeed, the operators need to think how to successfully approach a solution that requires a significant amount of expertise and creativity to evaluate possible scenarios where there are no clear answers. Instead of approaching this the traditional way, they choose an approach that has all the stakeholders working together as an alliance that shares the risks and rewards. This requires a new, agile approach for financial and legal contracts, as well as for the execution of the projects. It also enables learning and encourages greater experimentation than the traditional subcontracting model. Instead of defining the final system, successful execution requires the partners to focus on agreeing on a final goal where the ultimate solutions will be defined and implemented jointly during the project.

An interesting example of this type of joint approach to finding a solution was the construction project for the 2.3 kilometre-long road tunnel in Tampere, Finland. Rather than having all the stakeholders solve their own problems, their approach was to create an alliance for collaboration, as well as for sharing the risks and potential savings. This was the first major use of such an alliance approach in Europe. The principles of the alliance were joint decisions, trust, openness, ideation for improvements, sharing risks and savings, joint agreement of the final target cost of the project, and setting the revenue for each stakeholder depending on how well the jointly agreed target was achieved. The authors believe that these principles encourage partners to ideate various scenarios together, speak openly about the risks, raise any problems that occur as early as possible, and solve unexpected problems together rather than waiting for the other party to deal with issues alone. Ultimately, they have a common interest to succeed financially by exceeding the goals and avoiding the biggest risks. By the way, the tunnel project was finished ahead of schedule and under budget.

Are we already mastering our projects in the best way possible or is there room for further improvement? When the world is continuously changing, we should rethink our approach to complex projects. After all, one size does not fit all.

Kalmar provides cargo handling solutions and services to ports, terminals, distribution centres and heavy industry. We are the industry forerunner in terminal automation and energy-efficient container handling, with one in four container moves around the globe being handled by a Kalmar solution. We improve the efficiency of your every move through our extensive product portfolio, global service network and solutions for seamless integration of terminal processes.

Recent Comments