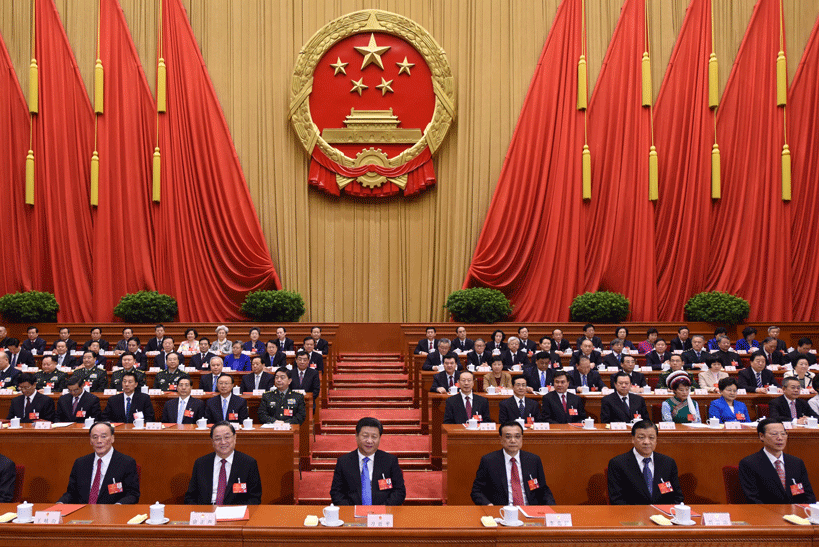

On the last day of the annual Lianghui (two sessions), China’s NPC delegates almost unanimously approved the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020). For all intents and purposes, it is Xi Jinping’s plan: for the first time in approximately three decades, the original briefing on the draft was given by the President himself at the Party’s Fifth Plenum, rather than by the Premier. Mark Rushton, Senior Director at FTI Consulting, and Kevin Ma, Director at FTI Consulting, dissect the plan, outlining the main themes—as well as the opportunities and implications for investors—that lie within.

On the last day of the annual Lianghui (two sessions), China’s NPC delegates almost unanimously approved the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020). For all intents and purposes, it is Xi Jinping’s plan: for the first time in approximately three decades, the original briefing on the draft was given by the President himself at the Party’s Fifth Plenum, rather than by the Premier. Mark Rushton, Senior Director at FTI Consulting, and Kevin Ma, Director at FTI Consulting, dissect the plan, outlining the main themes—as well as the opportunities and implications for investors—that lie within.

The context of the 13th Five-Year Plan (13FYP or Plan) is the ‘new normal’, a phrase first coined by President Xi Jinping in 2014, to describe China’s economic status quo. Positioned as an active economic transition, it denotes three changes in the Chinese economy: a gearing down of China’s development speed from high to medium-level growth; a shifting focus from industrial production and manufacturing to services; and a focus on innovation and consumption as drivers of growth rather than investment and exports.

China’s five-year plans are not action plans. They are instead intended as broad sets of overarching social and economic development guidelines to direct policy-making and resource allocation at all levels of government. In doing so, they are also intended to induce industry—state-owned and private alike—to re-orientate their strategies and focus their investments in line with promoted industry sectors and priorities.

Xi’s ‘master plan’ is designed with the overarching goal of developing China into a “moderately well-off society” in mind. To do this, the government has again set a hard target for the country’s GDP growth. Annual economic growth for the coming five years should average at least 6.5 per cent, a goal that would see a doubling of China’s GDP and per capita income between 2010 and 2020. While the range underscores an appreciation of the need to sacrifice some of the speed of growth to restructure the economy, discarding hard GDP targets would likely have instilled greater confidence among those wanting to see evidence that the reform agenda was to take precedence over growth.

Five key development themes are central to the 13FYP. Two of them—innovation and shared development—are given prominence in the State’s primary planning document for the first time. They sit alongside the more familiar priorities of green growth, coordinated development and opening up. Together, these are the five major trajectories of China’s next five years.

- Innovative development: creating an innovation nation

This 13FYP is the first ever Party document in which innovation has ranked first in the ordering. Driven by the pre-existing concepts of Made in China 2025 and Internet Plus, China has vowed to take decisive steps to upgrade its manufacturing capabilities in line with the innovative and smart technologies that are expected to govern future industrial production. The Plan also calls for companies to harness the Internet and big data to improve the daily lives of China’s people. However, the Plan still does not provide any greater clarity on how China intends to transition from a country that is already spending a significant portion of its GDP on R&D to one that is generating genuine innovation.

Foreign investors who can help advance China’s innovation capabilities stand to benefit. Opportunities exist in areas including energy, environmental protection, biotechnology, IT and high-end manufacturing, though domestic technologies will likely still be promoted in strategic or national security-related areas.

- Coordinated development: bringing China closer together

The coordinated development goals aim at addressing the gulfs in industrial production and consumption between the coastal and inner regions of China. With the march of urbanisation, the Chinese Government is encouraging foreign investors to ‘go west’ from their traditional coastal clusters to mid and western regions. With potential opportunities likely to emerge in lower-tier cities, a geographic readjustment of investment and vertical penetration into lower tier markets may become critical to maintain high growth in some industries.

- Green development: a lean and green economy

The 13FYP period will witness a focus on both sustainable production and consumption, as well as continued changes to China’s energy mix and infrastructure, to increase the proportion of clean and renewable energy sources. China will also support technology R&D and the further commercialisation of carbon emission reduction, energy-saving and efficiency-improvement technologies. While foreign environmental and renewable energy companies have long suffered market access restrictions, the emphasis on green development should lead to increased opportunities as the country encourages the uptake and deployment of globally-leading environmental products and solutions. Also, as sustainability has long informed the lexicon of many MNCs in China, it is a concept they will be able to leverage not only to benefit their businesses but also to build favourable platforms from which to engage various public and private sector stakeholders.

- Open development: looking outside

Many commentators understand China’s commitment to opening up to singularly mean a liberalisation of China’s marketplace for foreign investment. However, this is only a small part of the story. Opening up also relates to relaxing domestic market restrictions for private Chinese companies. More significantly, it also relates to the loosening of restrictions for—as well as active support to encourage—domestic companies to invest in overseas markets. An understanding of these additional aspects of China’s opening up policy explains why many foreign investors have been underwhelmed by the speed and breadth of investment liberalisation since the promulgation of the Third Plenum’s Decision. The 13FYP does little more than reaffirm China’s stance on its opening-up policy as iterated in the Decision.

The Plan promises a national rollout of the negative list system for foreign investment, which will undoubtedly bring opportunities for companies in many sectors to access China’s market. However, foreign companies should not expect China to fully shake off its protectionist tendencies that continue to curtail full market access. Many foreign business leaders will likely be disappointed that the Plan doesn’t emphasise the theme of the ‘market-led’ economy as strongly as the Decision did. Further, the Plan reiterates that SOEs should continue to be the backbone of China’s economy, dominating crucial sectors. While further SOE reform is mooted, additional aspects of the Plan will raise concern among foreign companies concerned that reform efforts following the Decision are yet to take hold in the area of SOEs. For example, China has committed to position a group of major Chinese MNCs to become global leaders in their respective fields. This point also relates to China’s increasing encouragement of outbound investment, which we are already witnessing this year with the spate of global M&A transactions by Chinese firms. Such outbound investment is set to continue to grow throughout the next five years. This will provide opportunities for foreign investors to attract Chinese investment and also for foreign professional services firms to support Chinese companies going global.

- Shared development: a real sharing economy

The concept of shared development relates to the objective to distribute the fruits of China’s three decades of reform-based growth to the Chinese people en masse. Key policies include poverty alleviation, universal and fair access to education, a ‘healthy China’ and an end to the one-child policy. A Chinese baby boom triggered by the ‘two-child policy’ will not be an overnight phenomenon but it will certainly have far-reaching consequences for consumer-facing businesses as the proportion of children in China’s demographic is set to increase. Foreign investors will likely also be able to seize breakthrough opportunities derived from healthcare reform as the ‘healthy China’ programme is rolled out, with the government encouraging the establishment of wholly foreign-owned healthcare institutions and elderly care facilities.

The 13FYP is not a game-changer. The development themes it contains closely reflect those already outlined in the Third Plenum’s Decision nearly two and a half years ago, when Xi cemented his vision of how China must respond to the realities of the ‘new normal’. While there is nothing new of note in the Plan to indicate marked improvements for foreign industry, this is not to say that it isn’t significant or that it doesn’t present opportunities.

China’s slowing growth during the 13FYP period will certainly pose challenges, but the ‘new normal’ also presents opportunities. Foreign companies have more experience operating in markets during times of slowing growth and are generally better equipped than their Chinese counterparts with technical expertise and operational excellence to respond to changes. The Plan is an undoubtedly crucial document to understand China’s future trajectories during the ‘new normal’ and to determine opportunities that might impact how companies choose to hone their business plans. This is particularly the case for those companies that foresee possibilities to move into new spaces that could provide significant growth potential or that were not previously accessible. In addition, the Plan should also be regarded as a communications guide for firms to position themselves in-market. In doing so, companies should demonstrate how their businesses are aligned with its tenets and can help the government achieve the country’s principal development goals.

Now that it has been rubberstamped by the NPC, the Plan will cascade downwards over the next few months to provincial, local, regulatory and other government entities. These authorities will be tasked with developing their own, more actionable, sectoral, industrial and local five-year plans that will have more direct impacts on companies operating in those areas. As these authorities will themselves need to determine how to mould their own plans in line with the central-level document—which purposely lacks clarity on how the development themes and concepts will be transformed into reality—there is therefore the possibility for companies to engage with these authorities to shape the lower-level plans. The window of opportunity for this is now.

With more than 30 years of experience advising management teams in critical situations, FTI Consulting Strategic Communications helps its clients use their communications assets to enhance and protect enterprise value. In addition to being the No. 1 global M&A communications advisor, FTI is a global leader in public affairs, financial communications and corporate reputation. With approximately 700 consultants in 28 key markets around the world, FTI combines global reach with critical local knowledge across domestic and cross-border engagements. To find out more, please visit www.fticonsulting.com.

Recent Comments