By examining the quality of a country’s institutions relative to its gross domestic product per capita, a clear pattern emerges.

By examining the quality of a country’s institutions relative to its gross domestic product per capita, a clear pattern emerges.

Antonio Fatás and Ilian Mihov from INSEAD explain that there are two stages of development: in the first stage, a developing economy can achieve high growth regardless of the quality of its institutions; in the second stage it is a different story – countries with low-quality institutions do not become rich. The indicators of institutional quality used in this analysis are voice and accountability (i.e. democracy), political stability, quality of regulation, control of corruption, government effectiveness and rule of law. As China looks to continue its growth trajectory, addressing the need for reforms in these areas becomes crucial. Rule of law, they say, plays a central role.

Over the past 35 years China has grown at an unprecedented rate, which has helped to lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and has led to a dramatic change in the economic structure of the country. But how long can China’s economy continue to grow? Not much longer, we suspect, unless the country engages in deep structural reforms that improve its institutions. It’s well known that countries’ economic performance is related to institutional quality, which is gauged by factors like political stability, government efficiency and the prevalence of corruption. China has sustained high growth rates in recent years despite its poor institutions because institutional quality is relatively less important in developing economies.

The argument that institutional quality is important for growth is not new and many have written about it, but our emphasis is on the changing relationship between institutions and growth at different stages of development. In the early phases of growth the relationship between institutions and income per capita is very weak (no need for radical reform) while it becomes very strong for higher levels of development.

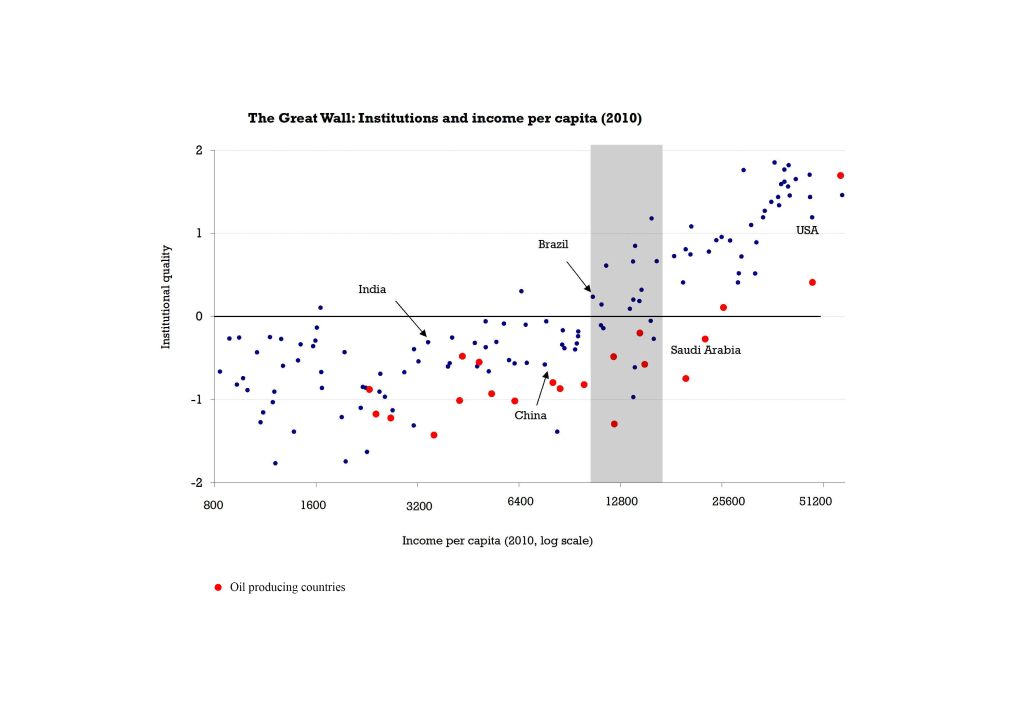

In the chart below we show the relationship between institutions and income per capita (in USD) in 2010 (institutional quality is measured as the average of the six governance indicators produced by the World Bank;[1] gross domestic product (GDP) per capita is adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP)).

The chart suggests that there are two phases of growth. A first one where institutional reform is less relevant. When we look at the chart we see almost no correlation between quality of institutions and income per capita for low levels of development, i.e. in the lower left area. To be clear, not everyone is growing in that section of the chart so it must be that there is something happening in those countries that are growing (moving to the right). Success in this region is the result of good ‘policies’ in contrast with the deep changes in institutions that are required later (you can also call them economic reforms as opposed to institutional reforms).

The second phase of growth takes countries beyond the level of USD 10,000-USD 14,000 of income per capita. It is in this second phase when the correlation between institutions and income per capita becomes strong and positive. No rich country has weak institutions, emphasising the importance of reform as a requirement for continued growth.

In a note for the Harvard Business Review (2009) we called the grey region ‘The Great Wall’. Economies either ‘climb’ the wall to become rich or they hit it and get stuck. Economies that illustrate the notion of hitting the Wall are the countries from the former Soviet Bloc that collapsed in 1989 after not being able to ‘climb’ the Wall with its institutional setting (a centrally planned economy); or Latin American economies such as Venezuela or Argentina which have incomes around that level and do not seem to be able to take their economies to the next step.

We named that threshold ‘The Great Wall’ as a reference to China: a country that over the last decades has displayed the highest growth of income per capita in the world with a set of institutions that are seen as weak (at least relative to advanced economies). China is highlighted in our chart above and what we can see is that, while it is still in the first phase of growth, it is getting closer and closer to the Wall. As expected, the growth rate of China slowed down in the past few years and the discussions about reform intensified. It is therefore not a surprise that the current government of China recognises reforms as the only way to address the challenge of the next phase of growth.

Characterising the two phases of growth and making explicit the necessary reforms that are needed to go from one to the other is not an easy task and it is likely to lead to different policy recommendations for different countries. It is instructive to look a bit deeper behind the six indicators of institutional quality. They are voice and accountability (i.e. democracy), political stability, quality of regulation, control of corruption, government effectiveness and rule of law. Interestingly, the indicator that shows almost the same pattern as in this chart is rule of law.

It is important to gain a deeper understanding of this relationship but one possibility is that advanced economies, i.e. the ones that have ‘climbed’ over the Wall, have succeeded in establishing unbiased courts and efficient contract enforcement. This is needed in order to facilitate further division of labour, creation of complicated value chains where each producer, by specialising in doing one small task, becomes very efficient and thus contributes to bringing up the productivity in the country and, ultimately, income per capita. Of the six indicators, the rule of law seems to play a central role. If this is the case, then for China to continue its convergence to an advanced economy, it will be imperative to establish the appropriate rule of law.

INSEAD is widely recognised as one of the most innovative and influential business schools, ranked among the world’s best. We bring together people, cultures and ideas to change lives and to transform organisations.

With campuses in France, Singapore and Abu Dhabi, INSEAD’s business education spans three continents. Our renowned faculty members inspire more than 13,000 participants annually through our graduate degree programmes and executive education courses. Today, we have an unparalleled global network of 47,000+ alumni across over 160 countries.

Over the decades, INSEAD continues to innovate and conduct cutting edge research to provide participants with the knowledge and sensitivity to operate anywhere. We don’t just say we are the Business School for the World. We live it.

[1] http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.asp

Recent Comments